The Rachofsky Collection.

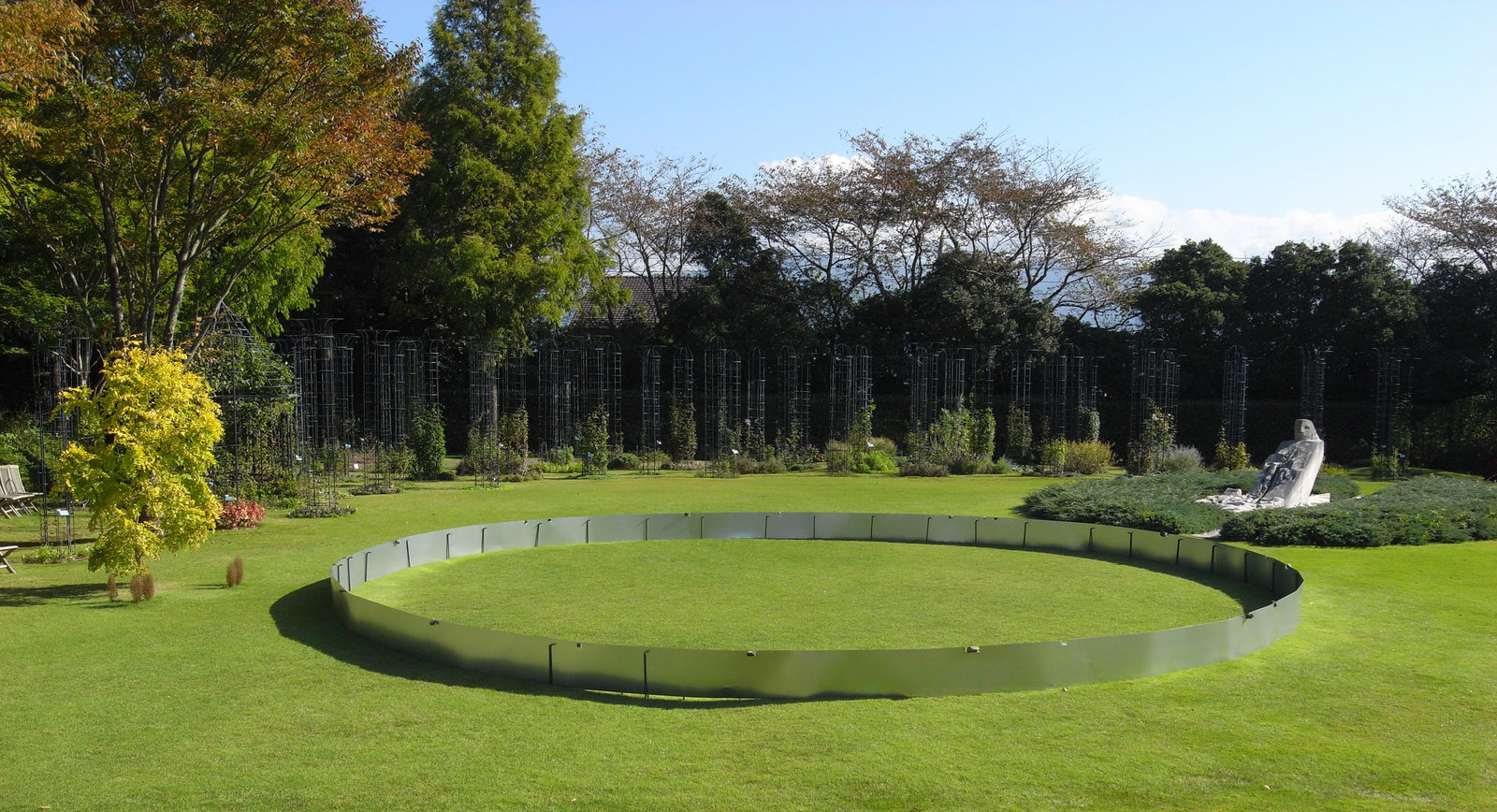

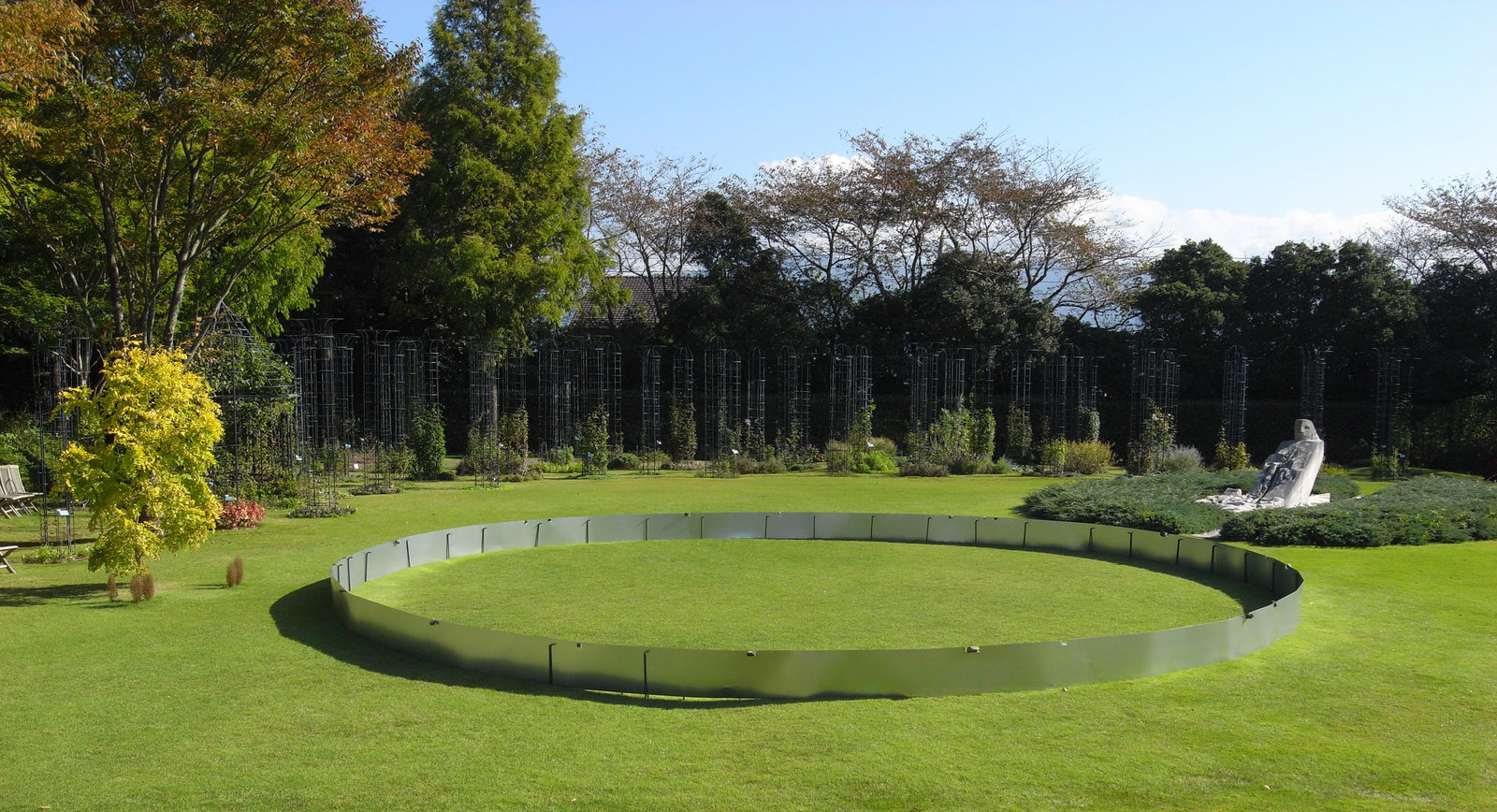

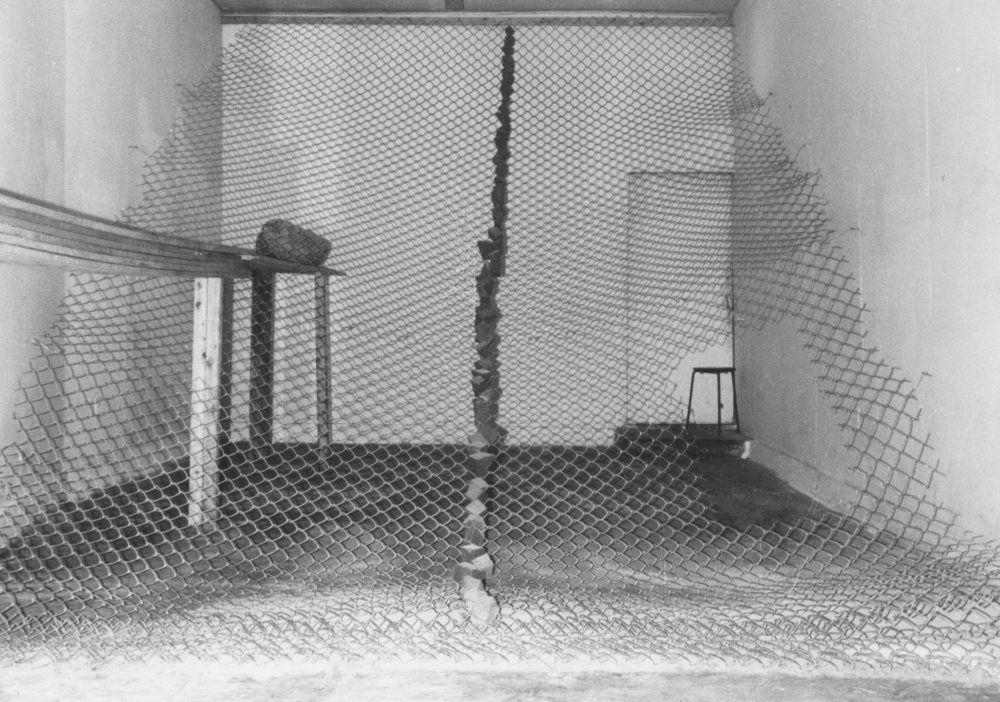

Blum & Poe Broadcasts in collaboration with Mendes Wood DM is pleased to present a historical survey of Kishio Suga, one of the leading figures of the Mono-ha movement in Japan. This month marks fifty years since he created his groundbreaking work Soft Concrete at Tamura Gallery, Tokyo, in 1970. Accessible on both galleries' online platforms, this online exhibition explores milestones in the artist's longstanding practice of creating site-based installations, alongside a presentation of his wall-based reliefs, works he has produced in tandem with his installations since 1969.

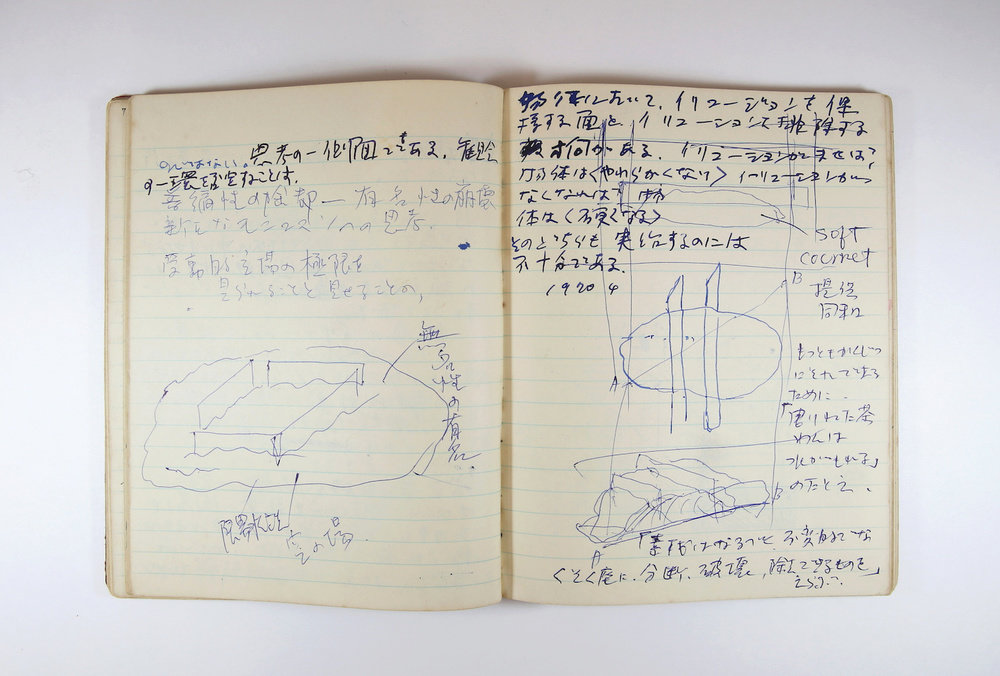

In a new video segment, Suga reflects on the experience of re-creating Soft Concrete in Los Angeles and Milan, the emergence of his perspective on the namelessness of "things" at the end of the 1960s, and his approach to making wall reliefs. Curator Mika Yoshitake has contributed a text which further examines the relationship between his installations and reliefs. This Broadcast also features the translation of his essay "Existence Beyond Condition" (1970) published just a few months before Soft Concrete was exhibited. This essay will be featured in a forthcoming anthology of newly translated writings by Suga, edited by Andrew Maerkle and published by Skira Editore and Blum & Poe.

To subscribe to our mailing list, please click here. To be in contact with our team, please follow the INQUIRE links below.

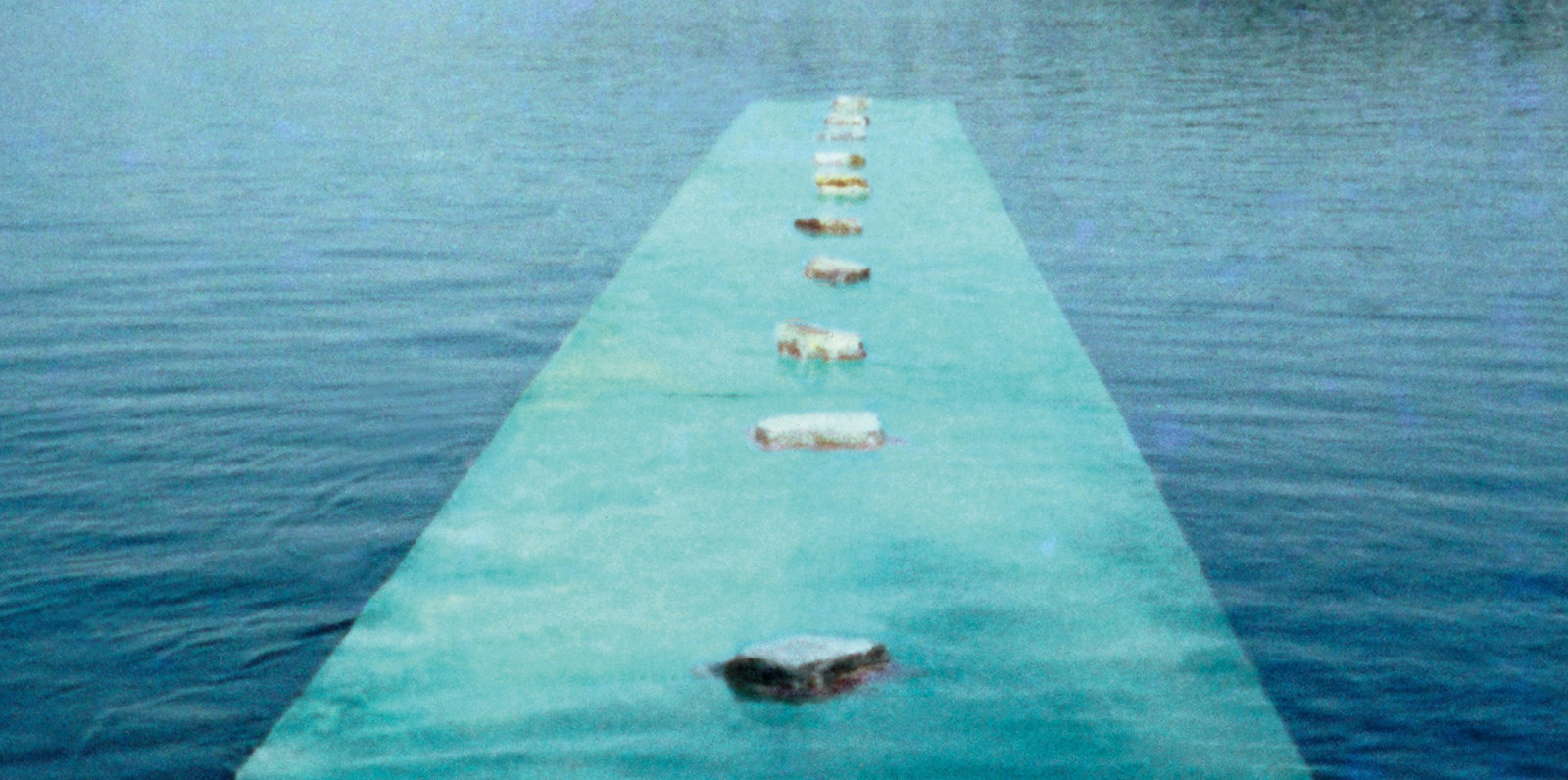

Tamura Gallery, Tokyo, 1970, photo: Kishio Suga.

When we happen to climb to a high place far from ground level, we sense more the fear that comes from our bodies not being supported, or from not having a single thing to support our bodies, than the fear that comes from our sensation of the height—and that is when we can perceive it as a place that is high. As there is no change to our standing on our feet, it feels as though we should be able to jump or hop around freely, but since there’s nothing but void some feet beneath the scaffolding, it means, when you think about it, that our freedom is being controlled by there being nothing there...

— Excerpt from Kishio Suga's essay "Existence Beyond Condition" (1970). Read the full essay and introductory text by Andrew Maerkle here: English/日本語.

The process of making something always involves a human act. Then, what I want to know is whether an intention or an idea that you have before you undertake an action is attached to the resulting thing. Do ideas always adhere to things? When we look at it from the end result, it must transcend your method—that is, it must deviate from your intention or idea, to clarify the essential state of mono as they exist. Am I wrong?

— Kishio Suga

On Kishio Suga's Reliefs

By Mika Yoshitake

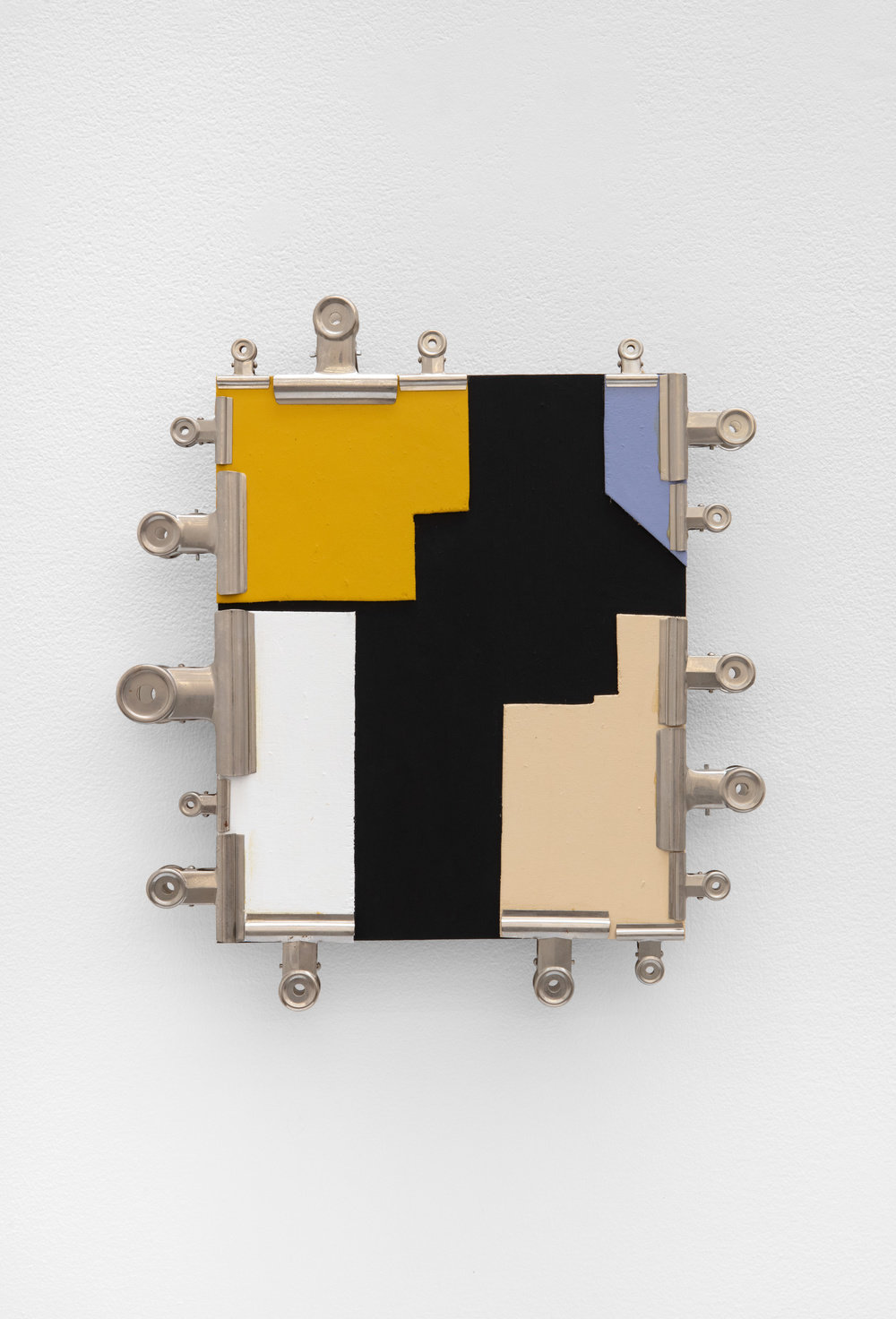

While Kishio Suga is best known for his site-based installations, another important feature of his practice involves wall-based reliefs, which he has continued to produce in tandem with his installations since 1969. These reliefs are smaller in scale and incorporate a range of everyday tools and items found in and around his studio like metal clips, braces, plastic air bags, along with scrap wood and branches from outdoors. Often painted in bright palettes, the reliefs at first glance appear like counterpoints to the expansive fields that question the perception of things in his installations. While Suga does not distinguish between the two media, they can perhaps be conceived as a lens into his daily labor of revealing, breaking down or erasing (what the artist refers to as) an “archetypal form” of a thing in order for a “material presence” to emerge.

As articulated in his landmark essay, “Existence Beyond Condition” (1970), a fundamental issue for Suga has been to defamiliarize objects that function as symbols, concepts, and signs. He continues to displace this schema of representation by showing the process in which a thing/object exists within a total field as a nameless entity. Suga’s early installations emphasize the interdependence of materials through balance and gravity contingent with the site. This state of interdependence among materials over time have evolved into a playful element in Progression of Spatial Alignment (1979), a floor piece, but nonetheless a logical progression to his reliefs, where six truncated branches lining wooden planks follow a linear, propped zigzag path above and along the floor—a recurring form in his installations, Units of Dependency (1974) and Contorted Positioning (1982). The organic curve of each branch is accentuated against the linearity of the planks. Suga begins to demarcate these spatial gaps in his reliefs such as Level Depth (2005) where black parallel lines outlining a triangular, hollow wedge between two wooden planks denote the union of organic and geometric structures.

It is impossible to clearly define the type of condition that forms an artist. Things are made because the ideal of making things exists. When we make a work, critique, or engage in a [political] struggle, these are all on the same dimension. We fall in love not with artists or works, but with the essence of a thing [mono], its state of being.

— Kishio Suga

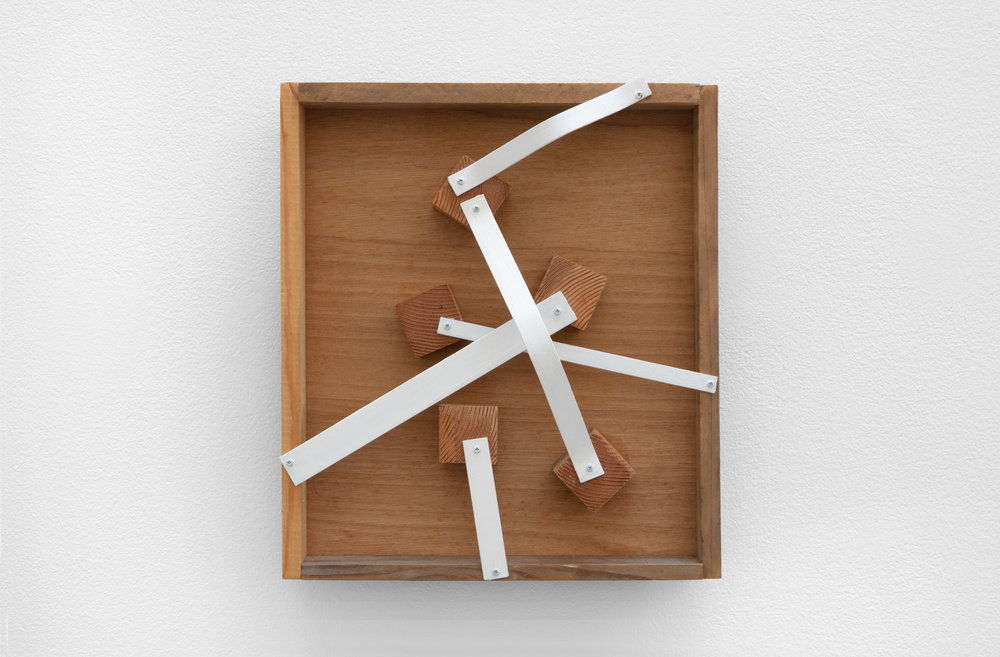

Often bringing negative spaces to the fore, Suga has set up a system of relational structures through which deliberate shifts, interstitial gaps, and overlapping of margins emerge. One system is compression—dispersion wherein geometric clusters are gathered around an organic form such as Accumulation of Fragmented Topography (2009), where approximately thirty wooden blocks shroud a two-pronged branch. Each of the blocks are marked by a painted white dot (except a lone black), effectively letting the branch recede behind a dispersion of dotted whites that pop along a topographic surface. In Elapsing Distances, Connected Points (2009), white painted metal strips branch out like roots between wooden cubes camouflaged inside a wooden boxed frame—a diagrammatic dispersal that echoes some of his earliest installations exhibiting kinetic tension like Left-Behind Situation (1972).

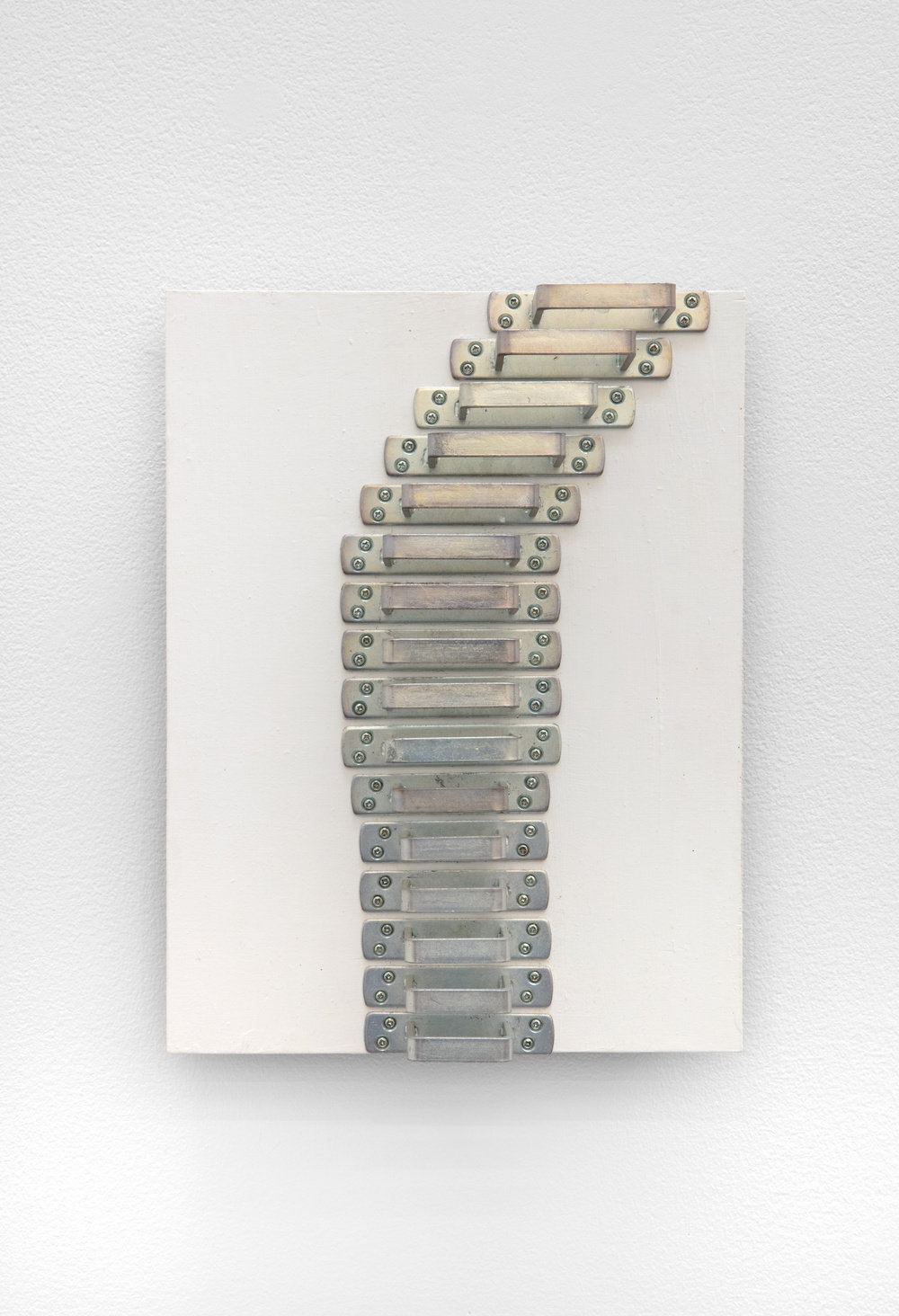

Another is gestalt, or the awareness of the body’s moving engagement where forms shift as the viewer walks from side to side and in front of the work. In Elapsing Scene (2011), a crescendo of metal brackets stacked vertically up, steadily veering right and protruding in various degrees, presents a mutable and fragmented experience of the present. Similarly, planks of painted white wood are placed across the surface in Differentiation (2008), presenting the illusion of a thin white line that cuts down diagonally when standing in front of the work, but unveiling its sharp dimensionality once one shifts position to viewing its side.

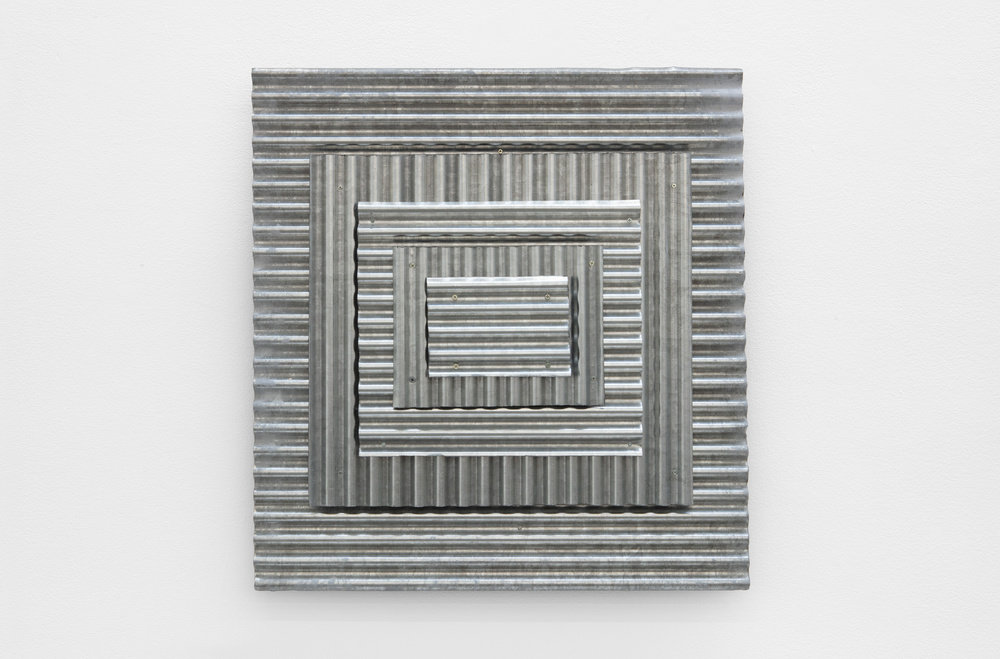

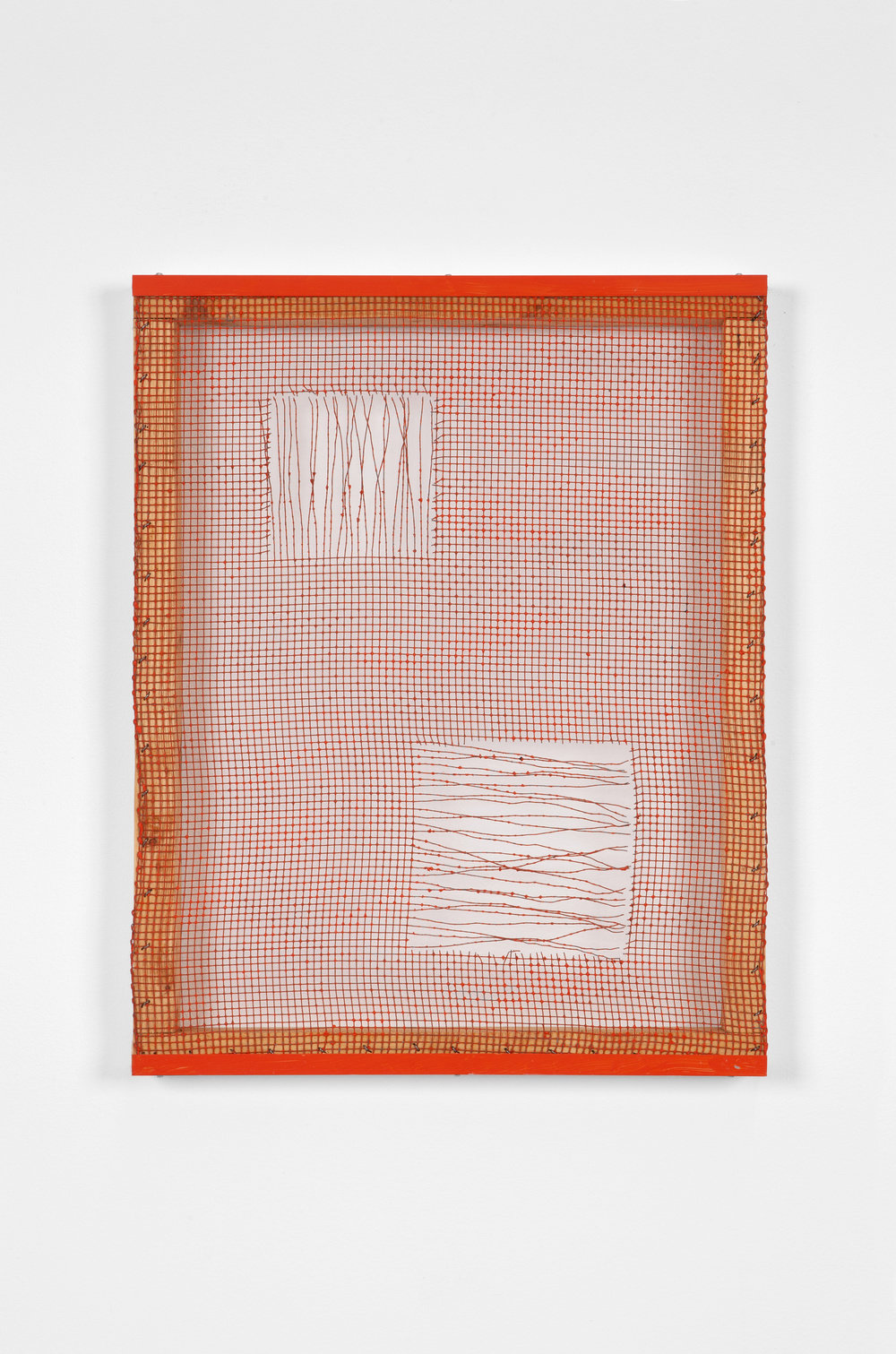

Finally, Suga’s facility with the intricacy of nets is particularly poignant in Gathered Elements in Union (2007) where he threads a golden wire square into a mesh grid to emphasize embeddedness. Playing with orientations, Interstices (2009) evokes hair line perforations across two squares of red mesh recalling the play of stones embedded in the wire netting in Condition of a Critical Boundary (1972). In Scenic Zones—Duplication and Direction (1996), Suga takes five square sheets of corrugated metal in decreasing sizes and places each on top of another, wherein the parallel lines of each panel shift from vertical to horizontal. Recalling the power of relativity in Charles and Ray Eames’ Powers of Ten (1977), Suga transforms this homogeneous matter into grids of shifting scale. Just like his installations, Suga’s reliefs continue to probe the ambiguity of perception, refusing to coalesce into a single totality.