Blum & Poe Broadcasts presents free and public access to scholarship and writerly ponderings from our publications archives.

In focus this week—excerpts from the upcoming publication New Images of Man edited by Alison M. Gingeras (Los Angeles: Blum & Poe, 2020).

From this project, Broadcasts features the essay A New Family of Man by Antonina Gugała.

Blum & Poe, Los Angeles, 2020, © the artists, photo: Makenzie Goodman

Primarily known as a pioneer of photography, Edward Steichen participated in pivotal events of the relatively short, yet fast-paced history of the new medium. Alfred Stieglitz’s student and collaborator, cocreator of the famous Camera Work magazine, and an active contributor to the legendary 291 Gallery, Steichen promoted photography as an art form. He exhibited his work at the gallery and was a key player in the introduction of European Modernism to America: Constantin Brâncuși, Paul Cézanne, Henri Matisse, and Auguste Rodin are among the artists he helped import to his adopted homeland in the US. Steichen, born in Luxembourg, was one of the most successful commercial photographers of his time, as well as a veteran of both world wars and an adept of aerial photography. At age fifty-seven, he had his first exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in 1936. A decade later, Steichen was appointed the director of MoMA’s photography department—a position he held for the next fifteen years, organizing over forty exhibitions that shaped curatorial practice from the late 1940s on.

During his tenure at MoMA, Steichen refrained from fulfilling his own artistic ambitions of continuing his own photography practice. As a curator, he remained faithful to the ideal that an exhibition “should also have an existence of its own, as does any other work of art.”[1] Family of Man was no exception. With the Cold War in full swing, and perhaps daunted by the moralistic nature of the anti-conflict exhibitions he had previously curated for MoMA (e.g. Korea - The Impact of War in Photographs, 1951), Steichen changed course, focusing instead on an optimistic, conciliatory survey of photography. MoMA’s epoch-making group exhibition was conceived as an affirmation of the universal human experience through the lens of photography. Family of Man celebrated the camera as a powerful, immersive tool for the promulgation of images and postwar humanist ideology. After the exhibition opened in New York in 1955, Steichen’s signature show went on a nearly seven-year world tour. According to his 1963 memoir A Life in Photography, between 1955 and 1962, approximately nine-million viewers in sixty-nine countries around the world had the opportunity “to see themselves reflected” in over five-hundred images depicting men, women, and children—making it the most popular photography exhibition to date. The show was followed by a publication with the same title, which quickly became the best-selling photography book in history. It is still in print today, more than sixty years later.

Between 1959 and 1960, Family of Man toured Poland, making stops in seven different cities. A few years into a photography practice that she began at the age of forty, local artist Zofia Rydet saw the exhibition in Warsaw. Steichen’s show made a strong impact on Rydet’s work and inspired her to complete her first photographic series, titled Mały człowiek (Little Man), exploring themes of childhood. She showed these images at her first solo exhibition organized in Gliwice in 1961 and later published a titular book. A compendium of black-and-white photographs of children shot in the vein of humanist photography à la Henri Cartier-Bresson, Rydet’s book was published in 1965 (reissued in 2012 by the Archeology of Photography Foundation) to popular appeal. The book—made in collaboration with Wojciech Zamecznik, one of Poland’s greatest graphic designers of the postwar period—constitutes a great example of the auspicious Polish People’s Republic school of design with its propensity for laconic forms and witty graphic solutions. Promoting neither communist nor capitalist ideals and carefully avoiding the superficial appraisal of her subjects, Rydet instead captures the individuality of each of the protagonists, who represent a number of non-Western countries (the photographs were taken in Albania, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Egypt, Lebanon, Poland, and Yugoslavia) that shared the universal experience of growing up in the global peripheries of a brutal post-World-War-II reality.

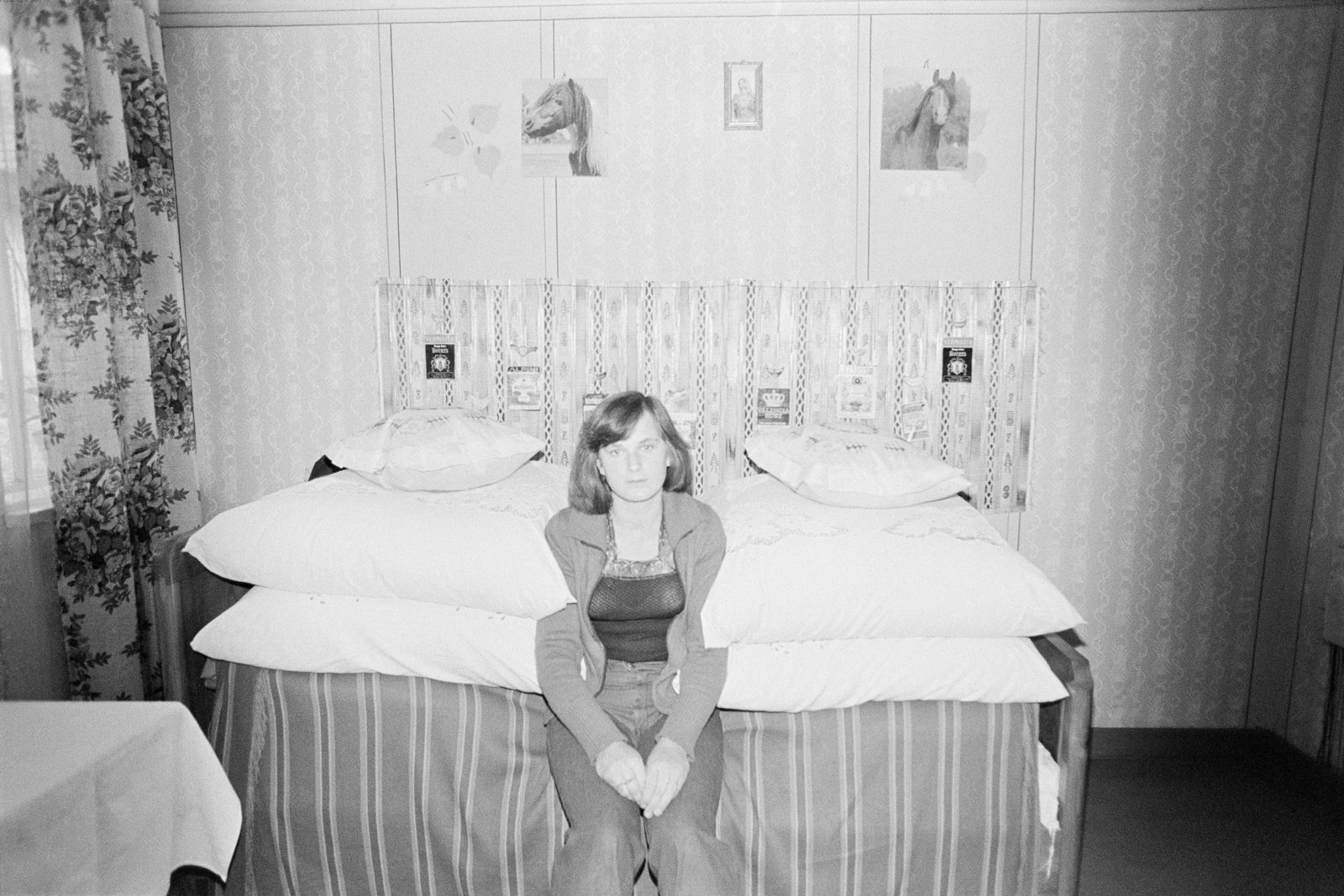

People and their environments were always the focal point of Rydet’s oeuvre. Zapis Socjologiczny (or the Sociological Record) was a larger-than-life documentary series, differing in style and scale from her earlier, more visually conventional works. In this project, Rydet amassed nearly twenty-thousand negatives, with each frame depicting interiors of ordinary households and their inhabitants. Shot in Poland and abroad, Rydet initially sought to document a rapidly changing rural landscape in the late Communist era by documenting interiors in the Southern region of the Polish People’s Republic. She also photographed subjects from urban centers and traveled to the US to document home interiors of the Polish diaspora. Rydet’s images were centrally composed, each lit with a single flash, and shot with wide-angle lenses, their subjects looking directly at the photographer. As Rydet described it:

“My initial assumption was that: the objects and the interior are more important, the man is just an element that describes this interior, thus he should be static, as if he himself were an object, therefore he must be seated in front of the camera, looking straight into the lens.” [2]

Self-taught, Rydet quickly realized the power of her protagonists’ direct gaze, freeing them from becoming passive objects in the frame and making their relationship to the interiors they inhabited far more complex than she had initially assumed. Each central subject functioned as a magnet in the image, pulling in the surrounding objects. Reminiscent of August Sander’s 1929 Antlitz der Zeit (Face of our time), this ambitious project was to become Rydet’s magnum opus. At age sixty-seven, she embarked on this quasi-scientific visual research journey in 1978 and continued photographing her subjects as part of the Sociological Record until 1990.

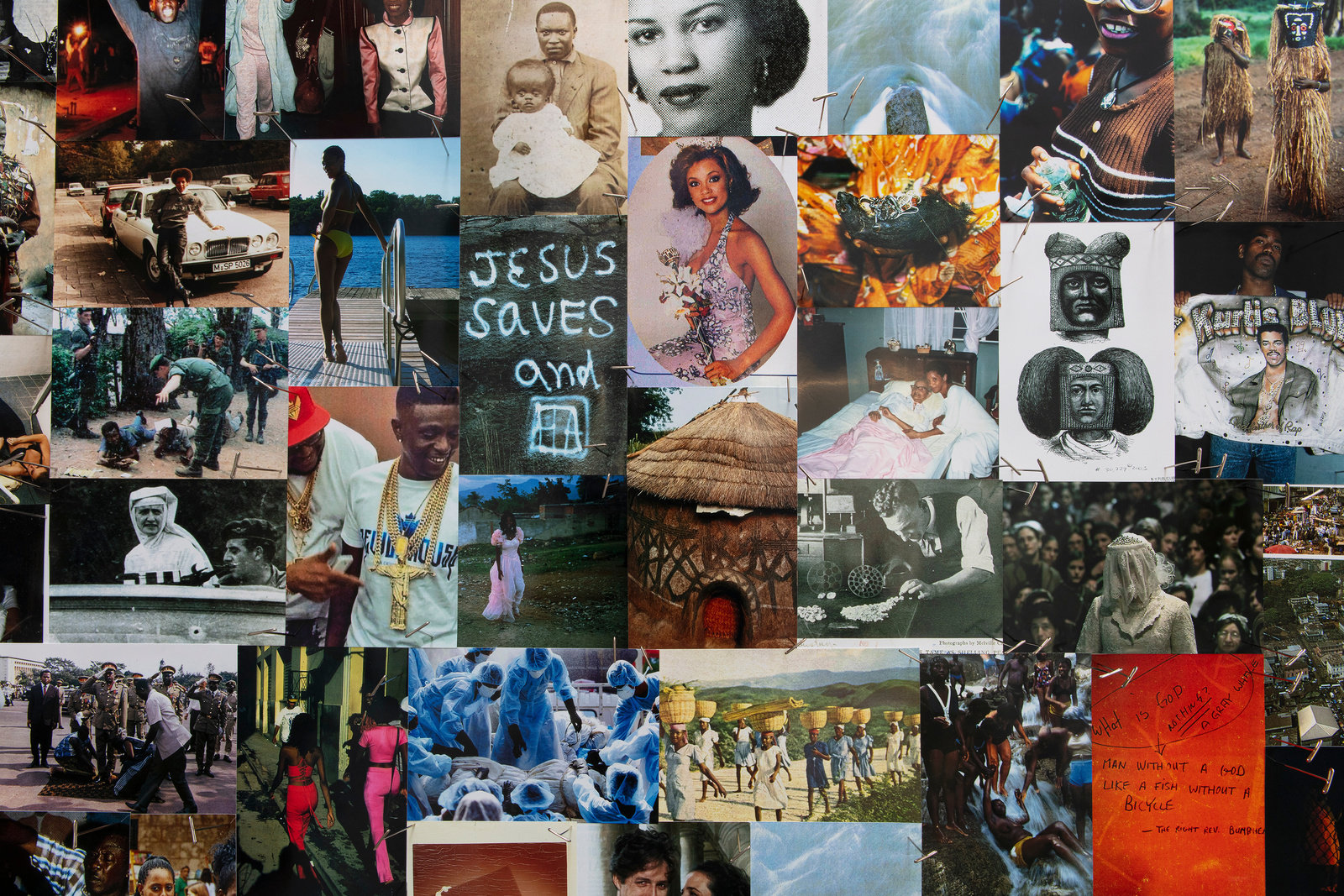

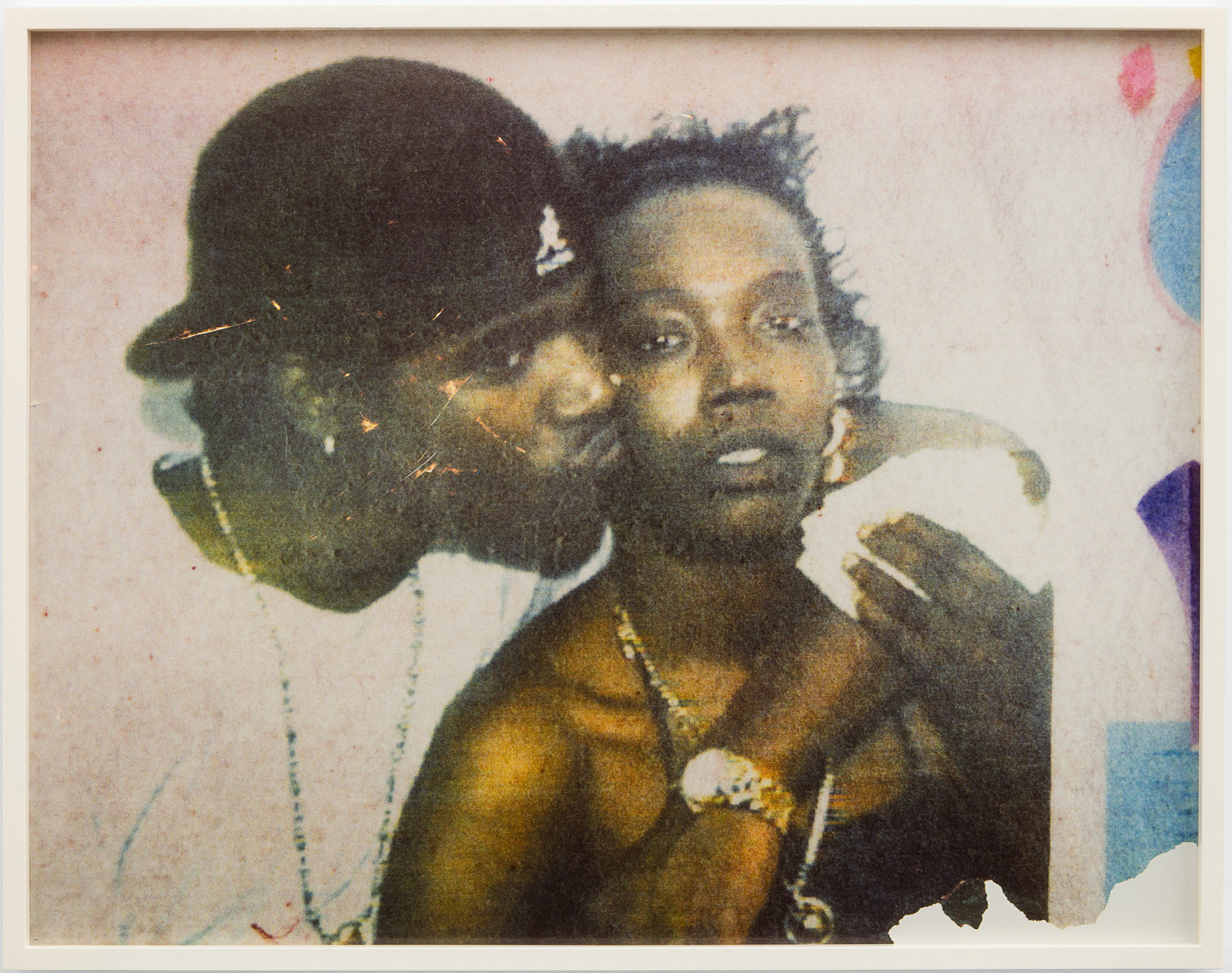

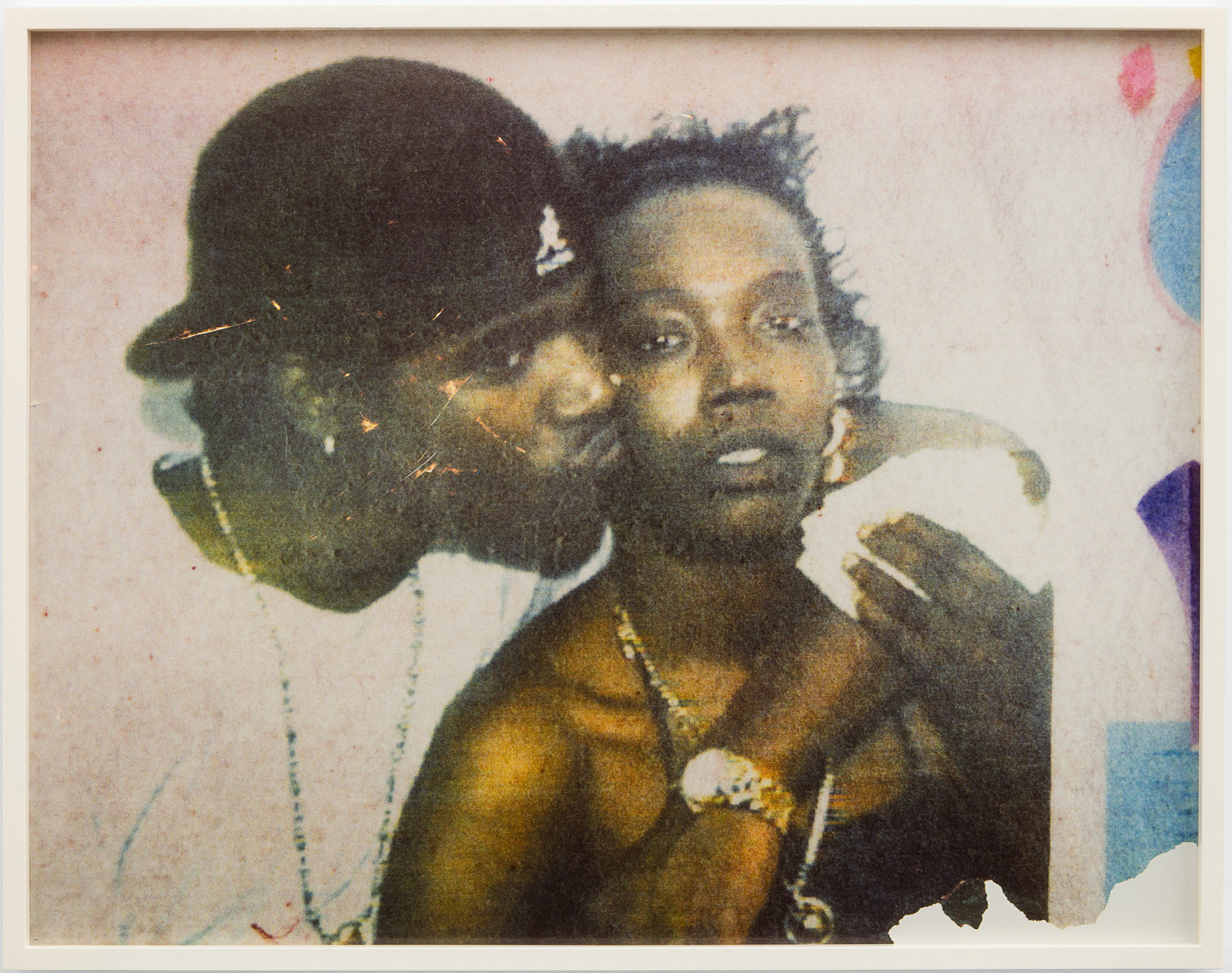

Across the decades and after the Cold War, the influence of Rydet’s documentary work can be found in the oeuvre of Deana Lawson. Born in Upstate New York in 1979, Lawson is an artist whose work observes the intimate experiences of African-American family life. Lawson grew up in Rochester, the birthplace of Kodak. Her photography practice is deeply bound with her family's own history—her grandmother worked for George Eastman (the founder of the Eastman Kodak Company) and her mother worked for Kodak. Like Rydet, who worked in sales before beginning a career as an artist, photography was not Lawson’s first profession. At Pennsylvania State University, Lawson studied business, but soon discovered photography, inspired by the artists Carrie Mae Weems and Lorna Simpson. A keen observer of her surroundings, Lawson’s gaze focuses on members of the pan-African diaspora. As she travels across Africa and the Americas, Lawson constructs an expanded family album in her photographs. Through the imagery she creates, crafting formal compositions that hark back to classical painting, Lawson observes the power relationships organically forming between family members, as depicted in ordinary scenes of everyday life. Zadie Smith writes,

“Lawson’s fullest subject is the diaspora itself … The diaspora is a broad and various thing, but one rich vein running through it has surely been the historical, economic, and personal necessity of making ‘something out of nothing.’” [3]

Lawson has a remarkable ability to capture power, beauty, and pride in her protagonists while simultaneously documenting the (often) precarious living conditions of her muses in commonplace dwellings. Vernacular photography is another recurrent trope in Lawson’s work. She draws inspiration from images of her own family album as well as found photographs. In Lawson’s hands, these colloquial images organically morph into conceptual works as she references these snapshots in her own work and creates intricate wall installations comprising a wide array of found imagery. Whether printing her own work on high-grade photographic paper or using readymade prints, Lawson pays close attention to the textures and materiality of her photographs—insisting that the viewer look at the pictures and not through them.

The New Family of Man challenges Steichen’s original populist paradigm. In lieu of Steichen’s stable of 273 photographers (who were predominantly American or Western European), we radically distilled this revision to two women artists from outside the original geopolitical spectrum while upending the original gendered and racial predilection. The black-and-white, stark language of Rydet’s grainy photography clashes with the painterly qualities of Lawson’s hyperreal color prints. Both artists frequently use the leitmotif of the curtain in their work—a liminal barrier separating the private and public spheres of family life. The curtain was also deployed in the 1953 design of the MoMA exhibition—a trope that is used in the current exhibition to recall Family of Man as well as invoke dreamlike memories of home. The viewer is confronted with two formally divergent visual narratives, which both depict the material culture and experiences excluded from Steichen’s original “family.” With the enthusiasm of a newly minted citizen, Steichen had an immigrant’s ambition to promote the American values of freedom across the globe. Separated by over seven decades, and developed within geopolitical contexts of oppositional ideologies, Rydet’s Communist-era documentation of the horror vacui interiors of countryside homes in the Polish People’s Republic resonates with Lawson’s carefully composed portraiture of the global African diaspora. Despite their differences, these artists comprise this redux of Family of Man—one that is united in their preoccupation with the politics of representation, landscapes of interiority, as well as the permeability of the private territory of home, and the public sphere of identity.

[1] Edward Steichen, “The Museum of Modern Art and ‘The Family of Man,’” in A Life in Photography (New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1963), chap. 13.

[2] Zofia Rydet, “O swojej twórczości,” Wydawnictwo Muzeum w Gliwicach, Gliwice 1993, accessed January 10, 2020, http://zofiarydet.com/zapis/pl/pages/sociological-record/notes/o-swojej-tworczosci.

[3] Zadie Smith, “Deana Lawson’s Kingdom of Restored Glory,” New Yorker, April 30, 2018, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/05/07/deana-lawsons-kingdom-of-restored-glory.