Blum & Poe Broadcasts presents free and public access to scholarship and writerly ponderings from our publications archives and network.

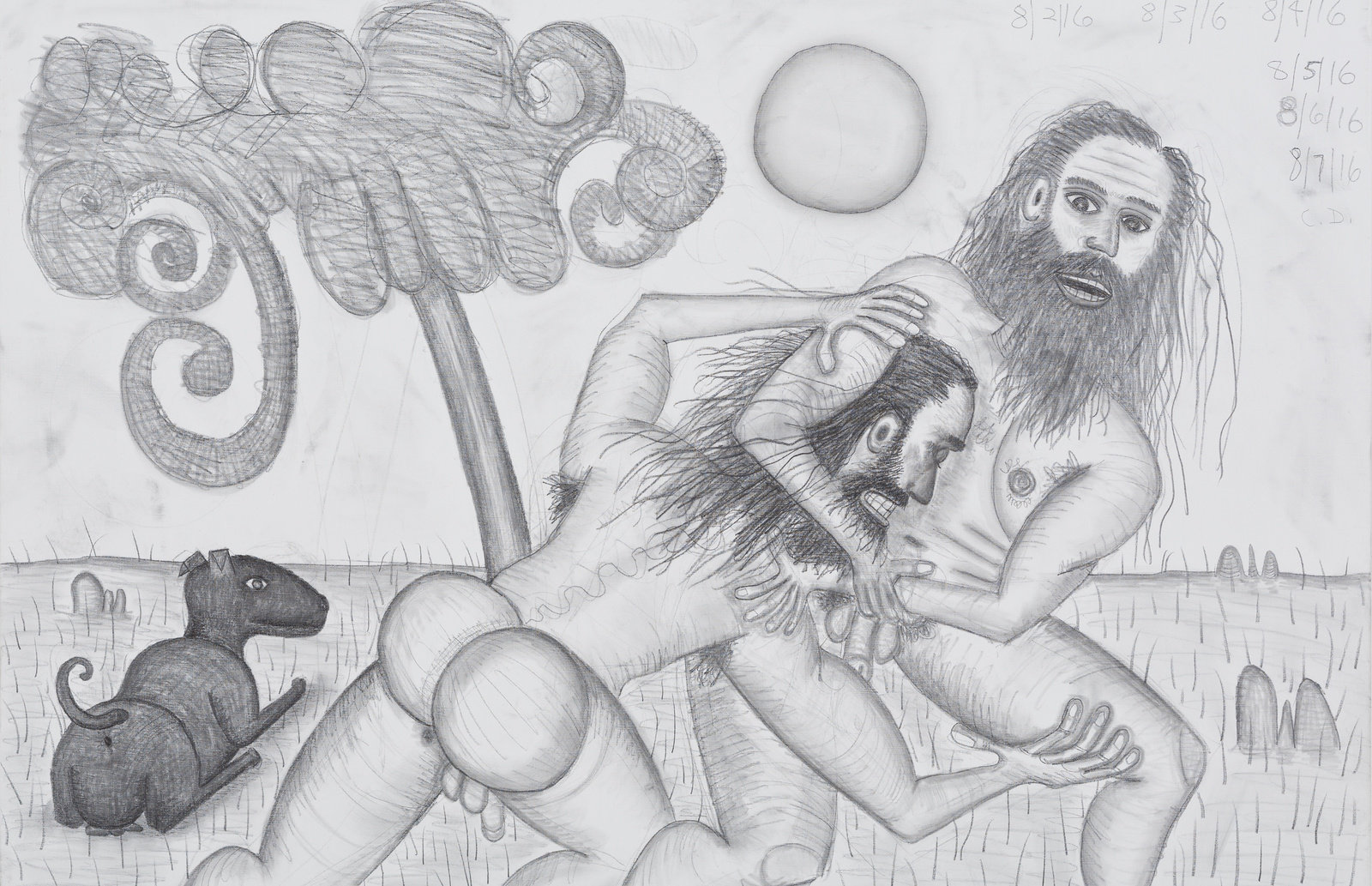

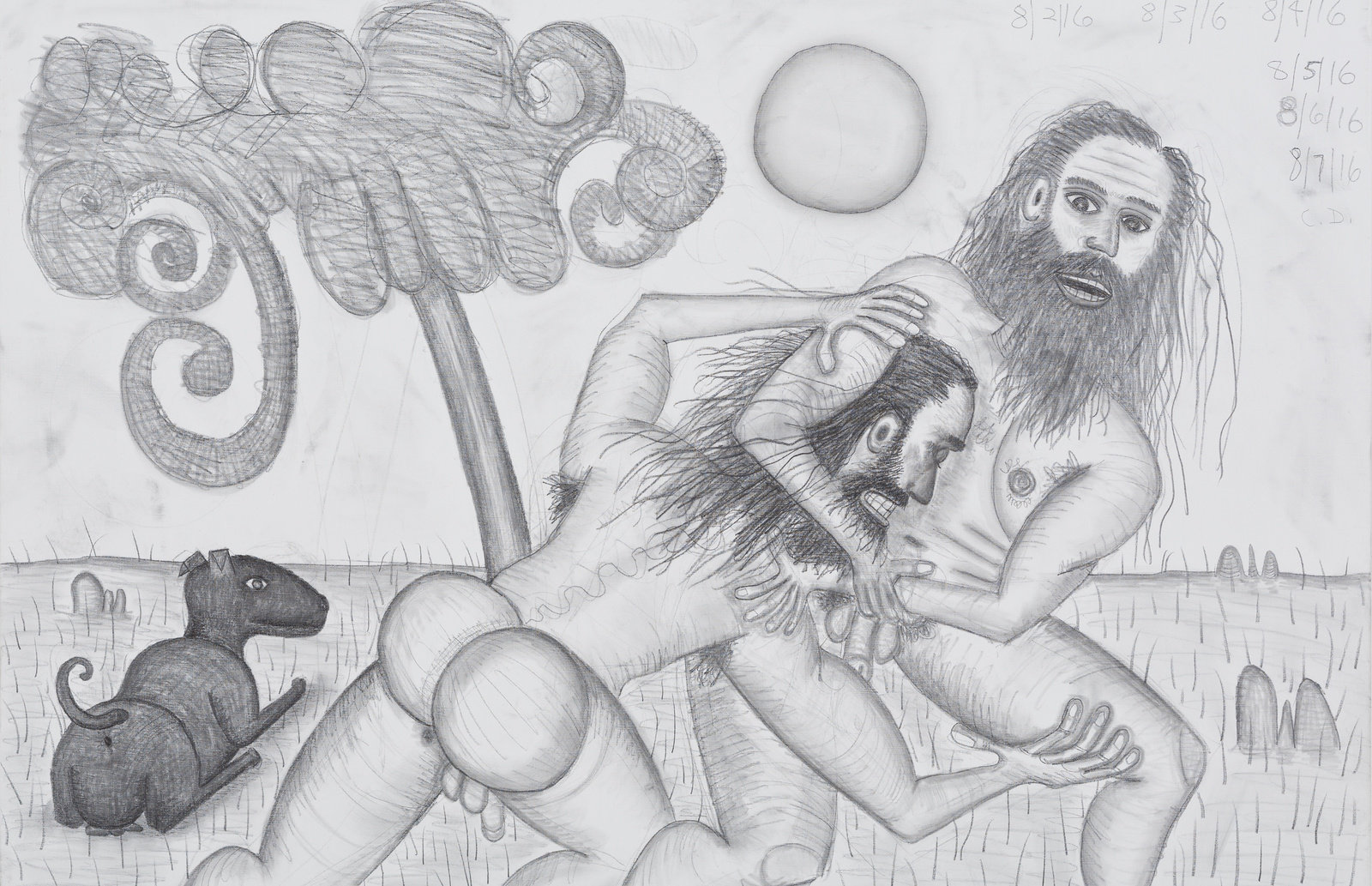

In focus this week—an essay by Alexi Worth, from Carroll Dunham's Wrestlers (Los Angeles: Blum & Poe, 2017), the catalogue accompanying Dunham's 2017 exhibition at Blum & Poe, Los Angeles. The book documents paintings which offer a vivid and unmistakably voyeuristic perspective of naked, male opponents: brute wrestlers, with their bulbous body parts; stringy, long hair and beards; scraped, rosy skin; brazen orifices and protrusions. Worth deconstructs Dunham's distinct style and mastery of abstract and figurative modes of painting and drawing, where the composition is as much the subject of the painting as is the charged imagery and uncanny world inhabited.

Wrestlers, AKA:

By: Alexi Worth

Brothers

How did we get here? Not just to this schematic savannah, with its lavender sky and single tree, but to this conception of painting—one so regressive and so deliberate, so nearly infantile and at the same time so assured, that it generates a reflexive demurral: the shock of the weird. More than any other living American painter, Carroll Dunham continues to sidestep expectations. In these new paintings of bearded, big-buttocked wrestlers, he pulls us, as he has done again and again, into freshly counterintuitive turf, into a world as far removed from our tech-addled daily lives as it is from any settled avante-garde idiom.

If our default expectation of serious painting is some kind of sly, hazy palimpsest, full of visual echoes—Albert Oehlen on a bad day—this is its opposite: sourceless and absurdly definite, not belated but aboriginal. The two wrestlers grimace and twist, grasping at arms and legs, pulling hair. All four hands and all four feet appear in every painting, and the bodies fit with a strange neatness into the rectangle, like bas-relief figures in a temple frieze. They appear to be evenly matched and identical—twin brothers working out their rivalry in some primordial Mediterranean or African setting. A puppy, watching timidly from the sidelines, projects a mock-sentimental or comical note. But the paintings as a whole never quite tip into real comedy, or at least, never signal that their violence is being mocked. Nor is there any intimation of an outcome. One wrestler sometimes seems to be on the point of toppling the other, but their bruise-covered bodies suggest that the advantage has swung back and forth, and will continue to, perhaps forever.

Wrestling is an ancient subject, and it would be easy to imagine an erudite backstory for this masculine stalemate. In the Iliad, Homer describes a match between Odysseus and Ajax, who “clasp each other in their mighty arms,” but cannot down each other:

Their backs creaked under the pressure of their strong hands, and the sweat ran down in streams, while many a blood-red weal appeared on their shoulders and ribs…

There are plenty of other mythological wrestlers—Gilgamesh and Enkidu, Jacob and the Angel—and of course there is a rich trove of wrestling imagery, from Hellenistic statuary to British homoerotic prints, from Hokusai and Muybridge to the WWF. And then there is another kind of wrestling, the fraternal wrestling of childhood. Growing up in unmythological Connecticut, in the late fifties and early sixties, Dunham had a younger brother with whom he wrestled. Two very different backstories: the iconographical and the biographical. Does either explain what we’re looking at here? I don’t think so. These grapplers are certainly not Connecticut Wasps. They’re too naked to be Hebrew patriarchs, too clumsy to be Greeks. For the real origins of Dunham’s imagery, as any Dunham follower knows, you have to look backwards, into his earlier work.

That’s because Dunham’s whole career has been exceptionally continuous, a single wayward spiral of thought. Back in the 1970s, Dunham started out as a young would-be minimalist, with an eye on Robert Ryman and Brice Marden. But their calm, blank canvases seemed more like an endpoint than a beginning. Where could painting go? Dunham’s answer was simple: it could begin again from nothing. Unburdened by nostalgia or academic skills, he devoted himself to graffitti-esque automatism. Like a new planet, his art evolved primitive life-forms, colorful bacterial soups swarming with improvised larval motifs. With their phallic “figures” and invaginated “grounds,” the Dunham paintings of the 80s and early 90s suggested a Hobbesian-Freudian formalism, full of interpenetrating peninsulae, grimacing mouths, and pubic cilia.

In the years that followed, his art moved through a strange double evolution—biologically forward and art-historically backward—to arrive at ever more recognizably human figures: first quarreling cartoon couples, then odious penis-headed alpha males. With the Bathers, things seemed to have culminated, ten years ago, in a childlike, full-bore figuration. And yet, while instantly recognizable as a nude Woman, Dunham’s Bather always advertised her abstract DNA. Her body looked composite, reassembled from geometric or biomorphic scraps of his own earlier paintings—compass buttocks, ruler arms, scribbled cilia dreadlocks. There was a kind of weird virtuosity in Dunham’s ability to cannibalize himself, to redeploy a few simple shapes so that, as if by some grand unconscious teleology, the molecular battlefields of the 1990s could morph into the womanly Arcadias of the teens. More than just a habit, self-recycling was a proof of Dunham’s autonomy. In cribbing from himself, he was avoiding all the temptations of external sources, of looking at photographs or film-stills or art history. Everything came from the petri-dish of his own mind. The germ line was pure Dunham.

Can that ever be true? Dunham is happy to acknowledge that self-generation, his own central premise, might be a motivating fiction, “a story I tell myself.” But it turns out to be a more plausible and powerful story than anyone might have guessed. In the case of the Wrestlers, it’s easy to see that they are masculinized versions of the Bathers; Cain and Abel to her Eve. They share the same bulgy anatomy, tangled black hair, floppy fingers and toes. You can even find instances of nearly exact repetition: two of the “Golden Age” canvases show an extremely foreshortened, feet-to-crotch view of a wrestler in midair—a pose that first appears as a diving female bather, back in 2013. The Bathers and Wrestlers are so similar, in fact, that their continuity looks almost trivial. And yet something important has changed: the memory of abstraction has dissipated.

The early Bathers seemed to have been conceived by someone more familiar with geometrical shapes and figure-ground reversals—in short, with Modernist painting—than with an actual human body. Line and color were voguing, not quite persuasively, as hips and breasts and trees. And so, for all their crudeness, the images had an implicit pedigree, a faint Mondrianesque accent. With the wrestlers, Dunham has let that go. These male bodies, pushing and grasping and clutching each other, seem palpably, unreservedly figurative. Vestiges of flatness (especially that lavender sky) are overwhelmed by grunting physicality, by a seemingly naïve depictive concentration. Perhaps that’s a function of wrestling itself, an activity that might be more corporeal than sex. In any case, the result is a group of paintings that move past the familiar terrain of cartoon abstraction, out towards the content-driven personalism of children’s drawings, underground-style comics, jailhouse reveries, and Outsider art.

Which is odd, not only because Dunham himself is a consummate insider, but also because the subject of these paintings is so historical, so canonical. The wrestlers’ nudity, semi-Assyrian hairstyle, and frieze-like arrangement make clear that they belong to some kind of museological antiquity, though we can’t specify when or where. The struggle Dunham evokes is something ancient and general, a piece of our primitive past that has been willfully semi-forgotten, and then reimagined in appropriately primitive terms. So what we have here is a double primitivism, a fusion of teenagerish graphomania and sober historical imagination; adrenaline and pessimism. It’s a fusion that feels disciplined and shrewd and weird, alive with subterranean memories we sense without being fully able to unpack.

Among them is, I suspect, one that deserves special mention: the memory of Matisse. In recent interviews, Dunham has sometimes mentioned Matisse’s “Russian” pictures—the famous 1910 canvases, The Musicians and The Dance, in which nude figures perform against a bare background of sky and earth. Beloved for their air of sweetness and innocence, those pictures are equally admired for their expansive, proto-color field beauty. It’s safe to say that neither quality brings Dunham’s Wrestlers immediately to mind. But compare the two sets of pictures side by side; compare their outlined bodies, and especially their flat, sky-dominated backgrounds. See if you don’t agree that Matisse’s reveries are ancestors of Dunham’s, or even come to feel that Dunham’s wrestlers are answers—fierce, dour ripostes to the willful sweetness of Matisse. However direct or oblique, conscious or intuitive, some kind of connection is unmistakable, and it reminds us that Dunham’s lunge towards naïve depiction is hardly a disavowal of Modernism’s ideals. We think we know those ideals: subjectivity; defiance; clarity; extremism. We just didn’t know that they could look like this.

Loners

At first, the most striking feature of these half-length figures is their forceful profile, like a Neolithic version of Dick Tracy’s. Dunham’s paintings of paired wrestlers suggest a kind of comaraderie, violent but intimate. This man is alone, unaccompanied even by the implicit presence of spectators. There’s no sense of a social encounter; he doesn’t acknowledge us in any way. Nor can we glean much about psychology, setting, or status. With his scuffed back, doughnut-like “wrestler’s ear,” and sinuous spinal tattoo, he could belong in ancient Ninevah or Tel Amarna—but also possibly present-day Williamsburg, or some neo-tribal future. His anonymity is a permission slip, allowing us to project and extrapolate. If we imagine him as a remote ancestor, the radiant undifferentiated blue beyond him might be the blue of pre-history. What can we say for sure, though? This painting is a portrait.

Normally, portraiture is empirical, or at least highly specific: it describes a living individual, or a person whose identity we care about, a VIP from myth or history. So portraiture is, of all pictorial genres, the least abstract. Dunham’s art, however, has always been passionately anti-empirical, built entirely from a slow accumulation of rudimentary visual ideas—the abstract DNA that I mentioned above. And even the paired wrestlers, while they have grown more fluently depictive than anything else in Dunham’s art, never suggest for a second that they are based on observation, or “real life.” Their balloon butts and wiener fingers are Dunham’s version of a corporeal pidgin, as emphatically plucked out of thin air as the crudest doodle. And yet, as Dunham has gradually allowed his art to evolve towards ever more nuanced figuration, he faces the hurdles of genre. Portraiture wasn’t really possible ten years ago. Even the Bather paintings only gradually developed faces and hands and feet. By now, though, Dunham has new options, ones that he seems unwilling to evade. From larval life forms, Planet Dunham has gradually arrived at the stage of Early Man. Individuality looms. Here Dunham has treated its challenges with a resourceful and unexpected delicacy. The anonymous veteran wrestler, turning his back on us, remains evasive, nearly abstract, a kind of gruff, economical, anti-portrait. And yet, because of his scale and cropping, he feels physically near, so near that we can’t help responding to him as a human presence, with its own peculiar dignity and even—though the grimacing ungainliness of the paired wrestlers would never have led us to expect it-- nobility.

Assholes

In the history of art, they don’t make much of an appearance until the twentieth century, when Picasso for instance sometimes ornamented his pneumatic nudes with a coy asterisk. Among other distinctions, Dunham’s recent paintings are the first to make assholes not just visible, but literally central, and to treat them with a bizarre, almost honorific solemnity.

For the past ten years, the apertures in question have been female. The Neanderthal Eve of the Bathers paintings was shown romping in primordial nakedness, typically with one leg up or both legs outspread. Between her massive curving buttocks, two graphic emblems appeared: a vertical line and a mini-circle—like a study, in estrus pinks, of an electrical outlet. These two orifices were unsensuous, diagrammatic, and public in a way that startled many viewers. “I just can’t look at that work,” more than one artist friend told me. Dunham made female nakedness feel newly explicit, newly implicating—just as much a visual affront as male nudity.

In some of the Woman paintings, Dunham even went so far as to connect the rectangle’s four corners with long ruled pencil lines, apparently to demonstrate that the tiny circle of the Woman’s anus is located not just approximately, but at the exact center of the canvas—the site where, in Leonardo’s Last Supper, Christ’s face appears. This perverse elevation might have been expected to read as a bawdy satirical gesture; instead it seemed oddly earnest. Dunham’s exactitude suggested a kind of fundamentalism (no pun intended): a principled insistence on biological basics. In his new quartet of “Self Examination” paintings, that insistence takes on new forms, at once more dour, more ridiculous, and more unsettling.

For most of us, the posture demonstrated in these paintings is impossible. No amount of time on any yoga mat will get you there. Not that many people, even the most impressively limber, would enjoy this particular kind of rectal selfie. In any case, by suggesting a physical continuity with the spectator, the image makes our actual wishes moot. Standing in front of each canvas, we find ourselves participating in a first-person encounter with our own folded body, pictured as dirty, near, and conspicuously male. Where the two thighs meet, the drooping package of cock and testicles flops down beside the navel, like a deformed face. Just above the genitals, set in a luminous triangle, is the solitary oculus of the asshole. Like a gun muzzle or Masonic Eye, it exerts a grim fascination, drawing our eyes inexorably back to the point of maximum vulgarity and discomfort.

This much alone would have made a bizarre and memorable sight: The infamous male gaze refocused unsparingly on its own abjection. But there’s more. In the bright yellow sky above the folded body hovers an eerie apparition, both comical and ominous. Is it a buzzard, a blackbird, a crow? Whatever it is, this black, origami-like bird is precariously near, its tail feathers even brushing against our buttocks. We can’t help recognizing that its long beak and tapering wingtips pose a distinct physical threat. In three of the paintings, our feet are lifted, apparently to bat the bird away, to defend ourselves from the avian rape that our posture seems to invite. Is the bird a phantasm of anxiety, conjured up by our own vulnerability? Is it an emblem of mortality, of death and disease, hovering like a toxic seagull, ready at any moment to penetrate and poison us? It’s hard to say no to these intimations, but at the same time, there’s a goofball, almost plaintive quality to the bird’s presence that offsets portentousness. Its fixed gaze seems less lethal than neutral, a blank, stuffed-animal stare. And the human posture below—the froggy legs, the dangling junk—seems too undignified for tragedy or melodrama.

Ten years ago, Dunham exhibited an even more undignified, abject, and unsettling image, in retrospect the first of his anal-centric tableaux. Square Mule showed an intersex creature bending over to fire a revolver into its rectum. It seemed an almost transparent image of self-destructive fury, keyed, one imagined, to the politics of the second Bush administration. The new “Self-Examination” paintings inherit Square Mule’s startling unslightliness, but are, bizarrely, more cheerful. Their direct address, bright sunflower skies, symmetry, and high contrast give them some of the optical impact of advertising. Their message, though, seems closer to the severity of an old Yankee headstone, with its winged death’s head coarsely carved in slate. Is it weird to associate images so grotesquely sexual with the iconography of the Puritans? Is it a coincidence that the great Puritan divine, Jonathan Edwards (another Connecticut native) titled one of his sermons, “On the Necessity of Self Examination?” That sermon, like most of Edwards’ writing, is a brilliantly unsparing exploration of complacency. Edwards tries to persuade his listeners to face the unfaceable, to cease being “blinded and muffled” by the comforts of daily life. I can’t help thinking that, inside Dunham’s discomforting recent imagery—of which the asshole is an inevitable apogee—there is something Edwards would have understood: a beautiful dour insistence that we face, in our imaginations, the facts.