Blum & Poe Broadcasts presents free and public access to scholarship and writerly ponderings from our publications archives and network.

In focus this week—an essay by Amy Tobin on the artist Linder, titled Linderism: The Red Period. This essay was published in the catalogue for the exhibition Linderism at Kettle's Yard, University of Cambridge, UK (Cambridge: Kettle's Yard; London: Koenig Books, 2020). Of Linder, Tobin says, "her work excites all six senses: touch, taste, smell, hearing, sight and the pyschic, and it moves from the expected locales of contemporary art—the gallery—through to the magazine or zine page, the book cover, the stately home, the runway and the stage."

More on the Linderism exhibition here.

Link to the online shop here.

Linderism: The Red Period

By: Amy Tobin

Linder is a monteur, a musician, an icon, a bodybuilder, a photographer, an art historian… The catalogue of Linder’s multiple identities could continue ad infinitum. Yet her many roles are also held together in one: artist. Linder’s practice breaks down the barriers of what we usually think of as art. Her work excites all six senses: touch, taste, smell, hearing, sight and the pyschic, and it moves from the expected locales of contemporary art—the gallery—through to the magazine or zine page, the book cover, the stately home, the runway and the stage. Even Linder’s photomontages, the works for which she is best known, are expansive. They cut into the surface of images, revealing the unconscious forces that shape our lives. Earlier works made in the crucible of 1970s Britain concern the hyper-sexualisation of consumer culture and the boredom of the nuclear family. Later works are more ambiguous: the source imagery is similar—pornography, fashion photography and lifestyle magazines—but is now supplemented by rose and ballet annuals, luscious food, and historic images. Often made in series, these new works invoke discrete meanings, even if the magic of the figure/ground reversal produced by photomontage juxtapositions remains consistent. The enchantment of Linder’s photomontages relies not so much on deception, on smoke and mirrors, but on the reverse: the explication, the scouting out and the revelation of visual culture’s deceptions. Her work in other forms similarly focuses on the margins or peripheries of histories, on the border or the edge of taboo. To engage with Linder’s work is to follow her to these dangerous grounds. This exhibition and publication takes the title Linderism, not because Linder’s work has a definitive look or character; rather the ‘ism’ here functions to pluralise, to emphasise the shift from singular style to transformative movement. Linder’s works vary in content, form and intention, but the theme of transformation is consistent. These transformations convert the banal into the radical, the patriarchal into the feminist, the normal into the esoteric, and they also refract the figure of the artist so she can encompass many things: engineer, model, medium, stylist, spiritualist, perfumer.

THE MEANING OF STYLE

Despite the proliferation of Linder’s many selves, her participation in the punk movement in the UK has sometimes overdetermined her biography and the discussion of her work. She attended the legendary Sex Pistols gig at Free Trade Hall, Manchester in 1976 and equally infamous concerts in London. This has led to some readings of her early work as tantamount to punk style, a style so pervasive that it has come to stand in for style itself. This was also true for the cultural theorist Dick Hebdige, who featured punk prominently in and on the cover of his 1979 book Subculture: The Meaning of Style. The cover is a graphic illustration of a gender ambiguous face, made up with heavy eye makeup, bright red lipstick and sharp fronds of hair, resembling the heavily greased and styled fringe of punk youth. A similar face appears in Linder’s early work too, before she began to make photomontages. Her first experiments in collage, using fabric, depict figures with heavily made-up faces. These are reworked in two further collages on cardboard, and again later in the monoprint heads made for the cover art of the band Magazine’s Real Life album (1978). These faces share the subcultural style of punk; the features augmented by makeup, and the hair fixed and moulded or close-cut, are stylised versions of the actual garb worn by punks. The earliest collages were transposed from photographs of two punk women Linder took at the now infamous Sex Pistols concert at Screen on the Green in Islington, London. Through this transposition the actual image of these two anonymous women becomes a generalised look, their features stylised by the dense blocks of coloured paper and felt. Linder’s perceptive reduction of the photograph to stylistic elements parallels Hebdige’s argument about the meaning of style for subcultural attitude:

The challenge to hegemony which subcultures represent is not issued directly by them. Rather it is expressed obliquely in style. The objections are lodged, the contradictions displayed … at a profoundly superficial level of appearances: that is the level of signs. [1]

Hebdige’s concept of subcultural style is certainly important for Linder. She is one of the punks Hebdige describes who sought ways to resist the uniformity shepherded by the state in post-war Britain. But more than that, Linder under-stood the importance of style and its operations for both individual resistance and cultural containment. Her work perceptively used style as material. She intervened in the exchange of ‘signs’ that Hebdige describes, exploring both the pervasive image world of normative consumer culture and the spectacular culture of punk.

Linder’s depictions of punk figures are far from documentary; instead they offer a meditation on subcultural spectacle. Take her linocut print of Jordan, the muse of Vivienne Westwood and shop assistant at Westwood’s and Malcolm McLaren’s punk emporium Sex, later Seditionnaires, on the King’s Road, London. Jordan’s image became synonymous with punk, and she at-tracted both adoration and vitriol for her scandalous hyper-sexualised dress. [2] Appropriate to Jordan’s status as a locus for punk spectacle, Linder’s print was made after an image of Jordan she saw in the British tabloid the News of the World. With Linder’s careful rendering the image has a hagiographic character that describes something of the ironic iconic culture of punk. The thick lines of the linocut print are used to outline Jordan’s bold hair and makeup, underscoring the graphic quality of punk style, and yet, as appropriate as the medium is, the print is also jarring with its juxtaposition of archaic form and radical content. There is an ethics to this, with Linder exchanging the large-scale distribution of the tabloid for the artisanal reproduction printed and circulated on a smaller scale. The apparent superficiality of punk style, and the rhetoric of its phenomenal character, is here incised into lino—a material made to be walked over—and made to last. The archaicism of the relief print process pro-duces an oxymoronic punk romanticism that Derek Jarman would later also alight upon in his own Jordan-inspired film Jubilee (1978). This linocut, like the Screen on the Green collages, shows Linder’s attention to style, and her early experiments with manipulating images before photomontage. Like those later works though, the Jordan print has a perversity that both cuts into subcultural hype and re-inscribes an objectified figure.

By 1977 the ‘death rattle of first-wave punk’ in Britain had sounded, and many of punk’s key players retreated from media attention in the capital to the more ‘bohemian’ North. [3] Less oriented around spectacle, the Manchester scene was more varied; subcultures intersected in club nights at Dickens, a gay bar, or in the city’s music venues. As a student in graphic design at Manchester Polytechnic, Linder was already part of the scene, and as activity developed she became more entwined in the vortex of music, fashion, visual culture and intellectual debate that quickly began to escape the narrow confines of punk style. It was in this con-text of creative cooperation – with musicians such as Howard Devoto and Pete Shelley, writers like Jon Savage, zine-makers Cath Carroll and Liz Naylor and the photographer Christina Birrer—that Linder made her earliest photomontages.

‘A SHEET OF GLASS WAS THE BED FOR THE BLADE’ [4]

In Rip It Up and Start Again, Simon Reynolds describes the move from punk to post-punk as a turning away from the anarchy of punk’s anti-intellectualism and toward a more cerebral and critical mode. This included the art school graduates who ‘turn to pop music as a way to sustain the “experimental lifestyle”’ as well as ‘the anti-intellectual intellectual ravenously well-read but scornful of academia and suspicious of “art” in all its institutionalised forms.’ [5] If Linder and her contemporaries rejected institutionalised art, that didn’t mean that post-punk adherents rejected historic artists; rather they actively sought a genealogy of avant-garde art and radical politics that went back to dadaism and revolutionary surrealism via the situationists. This lineage shaped the left-wing critique of punk and post-punk, but in the latter this was turned less toward the mobilisation of a political class than toward the transformation of consciousness in the listener or viewer. As Reynolds decisively puts it in relation to the formal experiment of post-punk music: ‘this radicalism was manifested through words and sound equally, rather than the music serving as a mere platform for agit-prop.’ [6] Linder’s photomontages were also more than agit-prop. Her juxtapositions of magazines aimed at women (fashion and interiors) and magazines made for men (pornography) sought to reveal the dynamics of desire and manipulation that shaped apparently mundane life. Her work did not simply pit objectified woman against sexualised man, but staged the imbrication of heterosexual sex and love in the social structures of marriage and consumerist homemaking. Her suitably sinister description of the process of cutting on ‘a sheet of glass,’ which was ‘the bed for the blade,’ emphasises the erotic violence of the act of photomontage, which can cut through the fragile surface of the domestic status quo.

In this, Linder’s work compares with the détournements of the situationists, who also used imagery from both advertising and pornography augmented with captions or speech clouds with explicitly Marxist messages. While détournements were interruptions in visual culture meant to snap the viewer to political consciousness, Linder’s work was more ambivalent. For instance, in three untitled photomontages from 1977, Linder retains the text from the base image of the photomontage. One reads ‘Romance,’ another ‘Out of the Blue’ and the last ‘Familiar culinary disasters, and how to avoid them.’ In each case the text takes on the tone of a withering critique of the images of heterosexual coupledom they represent. In the first, a woman is half-transformed into a tart, which the man gazes upon with a wandering eye, while his mouth-crotch looks prepared to take a bite. The surprise in ‘Out of the Blue’ comes in the form of cigarette burn holes in the woman’s face, while in ‘Familiar culinary disasters’, the faces of the two figures are distorted with new upside-down eyes and mouths—the woman’s jaggedly torn, the man’s perfectly cut. On the tray the couple hold together, a joint of meat is supplemented by a stapler with a clitoris at its centre. Culinary disaster becomes cunnilingus, or perhaps the obscuring (and centreing) of sexual pleasure in social reproduction.

Linder’s photomontages were more than détournements. Whereas the situationists often produced and printed their visual propaganda anonymously, and with the least interference, Linder’s works were always authored and carefully made, with materials gleaned from particular publications and sources. Similarly, her cuts and her juxtapositions were, and are, precise, down to the use of a very specific blade—Swann-Morton No. 11—as used by surgeons. In this Linder is closer to the dadaists. She has noted her interest in Berlin dada, and the artists John Heartfield, George Grosz and Hannah Höch in particular, which she encountered in art historian Dawn Ades’ pioneering 1976 study of photomontage, procured in Manchester’s radical Grass Roots bookstore. It was in response to Heartfield’s and Grosz’ anglicising of their names during the emergence of fascism in Germany, that she changed her name from Linda Mulvey to the Germanic Linder, at a moment when the English far-right were gaining a foothold. The relationship between art and life, as well as art and labour struggle in dada, was also important for Linder. The idea of the montage, and its maker the monteur, connected the artist to the mechanic or engineer and brought the issue of class back into view. Unlike the dadaists’ celebration of modernity and the machine though, Linder’s work—made in Manchester during the 1970s, when the city was entering into post-industrial decline—offered a view of the other side of modernity.

The dadaists were influential for others in the post-punk scene too, and this led to a number of collective projects that were loosely inspired by the Berlin dadaist clubs and groups. In 1978 Linder and the writer Jon Savage came together to make The Secret Public and then a collective portfolio of photomontages called Mixed Media Montages. Comprising works by Edward Bell, Linder, Ian Pollock, Savage and George Snow, Mixed Media Montages was a dispatch from the post-punk scene and an incisive critique of bourgeois Britain. Linder called it a ‘cultural post-mortem.’ [7] While other contributions engaged with world events, urban politics and masculinity, Linder focused on domestic scenes, mostly bedrooms and kitchens. These two rooms of the house stood in for the dual expectations of feminine domesticity: cooking and sex. Untitled (TV-SEX), one of the most famous of Linder’s works from the portfolio, is a case in point. In this work a couple sit ensconced in a comfortable living room, hands where each other’s genitals should be. Rather than enacting foreplay, the male figure fingers a remote control, while the female figure clutches a phallic vacuum cleaner. Both figures’ heads are replaced with television sets, oriented straight ahead and away from each other, showing scenes from a horse race. Here both man and woman are caught in the bind of respectable homemaking heterosexuality, where desire is sublimated by marriage and, in capitalist society, the consumer spectacle of domestic bliss. Linder’s juxtaposition of two categories of print—the homeware magazine and print pornography—breaks the veneer of bourgeois style and reveals the ‘secret’ structures that condition the patterns of everyday life: sexuality shrouded by domesticity.

The conceit of blindness or not seeing in these early works is crucial. Not only do they speak to a culture of distraction, and alienation, but more specifically they also allowed Linder to begin to deal with her own experience of sexual abuse, which was perpetrated by her step-grandfather through pornographic imagery. [8] The domestic structure of the family, what psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud called the incest taboo, provided a mask for this abuse and through this secrecy escalated its violent power. While this experience was never the sole motivation for Linder’s early work, which cannot be reduced to a response to it, her representations of secrecy and blindness, as well as her desire to use and transform pornographic imagery, were a means to contend with this experience.

© Linder

© Linder

ANATOMY IS NOT DESTINY

In recent years the photomontages have become associated with feminist politics. Linder was not directly involved in the activism of the Women’s Liberation Movement, but she was more open to feminism than her punk and post-punk contemporaries such as Viv Albertine of the all-woman punk band The Slits, and Vivienne Westwood, who saw women’s liberation as middle-class, sincere and censorious. Linder had long sought out books on or about women as well as feminist publications like Spare Rib, and as art historian Maria Buszek has noted, she enjoyed being part of a rich history of woman-centred activism in Manchester. [9] The politics of feminism were as influential to the photomontages as dadaism. Like her contemporaries Linder troubled the representations of women’s bodies in fine art, advertising and popular culture, but her feminism was also shaped by a Northern, post-punk and white working-class context that saw the possibilities for remaking the trappings of femininity for a different kind of glamourous embodiment.

Linder’s photomontages show the socialisation of gender oppression and its deleterious effects for both men and women, but other early works such as her lingerie masks, or photographs of Manchester nightlife, skewer heteronormativity and fixed gender roles. Linder’s candid shots in the nightclub Dickens document the culture of transgender performance in 1970s Manchester. This was also a place where the queerness of the post-punk scene could emerge beyond the machismo of other music venues like The Haçienda, the home of Factory Records. Around this time Linder made a series of lingerie masks that played with punk style. Made for men, they repurposed the frills, lace, clasps and suspenders of feminine lingerie, in contrast with the bondage gear favoured by punks, into half-face masks. Unlike the fetishising function of lingerie, made to split the woman’s body into parts—as filmmaker and theorist Laura Mulvey had described in her lacerating critique of the artist Allen Jones in Spare Rib—the masks concealed and transformed the face of the wearer, and obscured their vision. [10] This had two effects: one to disempower the objectifying gaze of the wearer, the subject of another of Mulvey’s essays, ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’ from 1974, and the other to render them reliant on their partner. [11] The masks proposed the reversal of the dynamics of sexual relations, so that power and weakness could alternate, and the spectacle of sexuality was redistributed. The masks were made while Linder was studying at Manchester Polytechnic; unable to justify the objects themselves to her graphic design tutor, Linder styled the masks S/M-style for a mock magazine spread featuring Devoto as a model. Playfully naming her brand ‘Limiting Accessories LTD’, Linder captured Devoto pouting for a kiss, with mouth wide open, and with a seductive but vulnerable look to the camera that enacted the reversal the masks invite.

If Linder created the conditions for de-masculinisation with her Limiting Accessories, she went on to explore the potential for exceeding her own limitations through body modification. In the late 1970s Linder became interested in building her strength, first by searching out the only Iyengar yoga teacher in the North-West at the time, and then later in 1979 at a gym in Manchester’s Moss Side. It was while registering for the gym that she picked up the name Sterling, because she needed a surname to complete her membership. In a notebook from the period Linder lists her potential names for the gym: Mandy, Diana, Judy, Pam, Shirley, Lilian. Eventually she settled on Pam Sterling, marking a new and temporary identity, one of many she subsequently made use of to obscure her identity after press and television publicity on the Manchester scene. Linder’s work at the gym was another point of merger between art and life. Influenced by the American bodybuilders Carla Dunlap and Rachel McLish, as well as North American photographer Robert Mapplethorpe’s photographs of bodybuilder Lisa Lyon, Linder sought to remake her own body, to feel her anatomy differently, and to excise the gendered expectations on her body.

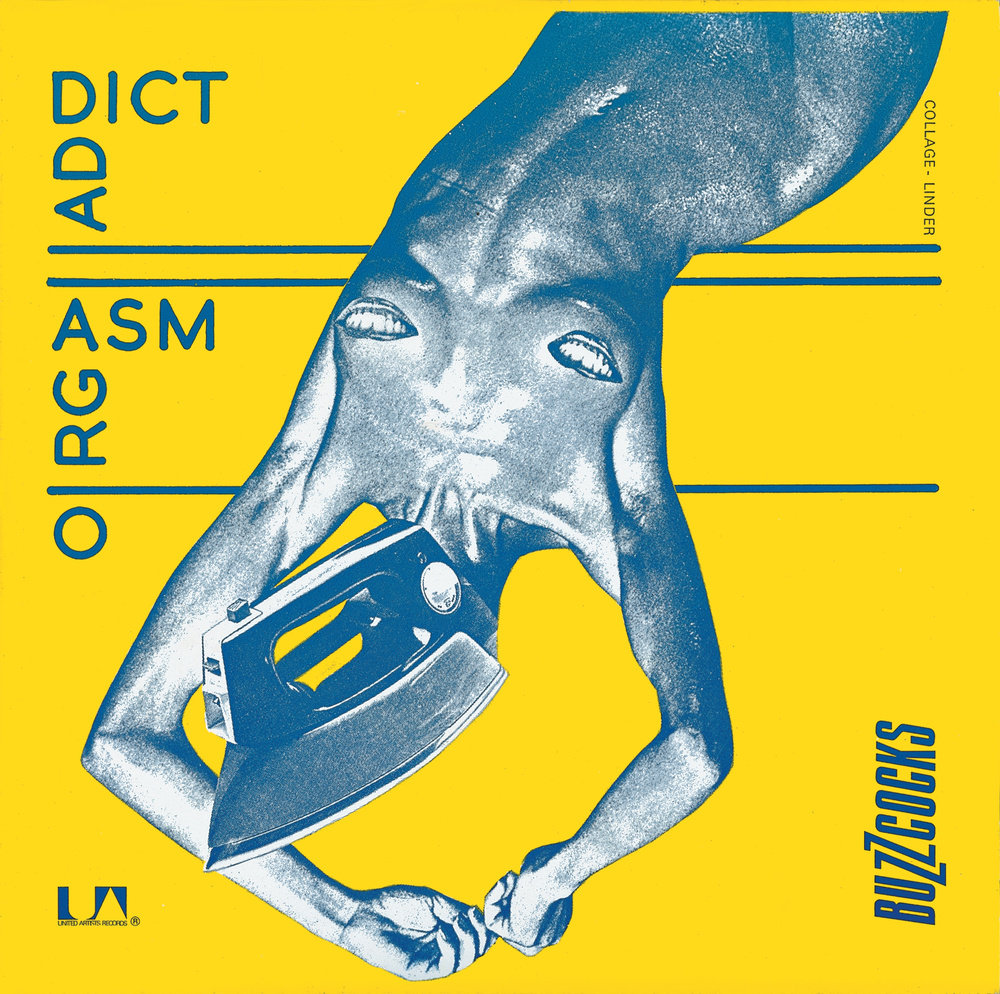

Linder’s bodily transformation exists now in photographs taken by Birrer and Benoît Hennebert. In one photograph by Birrer, Linder stands back to camera in strongman pose to show the strong triangle of shoulders, her narrow waist and muscular arms. Although coincident with the 1980s shift to ‘body beautiful’, Linder does not pose her physique after the feminine aerobic slim, but instead emphasises her strength. In The Book of Skin, Steven Connor discusses the importance of tautness and shine to the bodybuilder, which he com-pares to the second-skin effect of wearing leather or rubber bondage-wear. [12] Like rubber or leather, the tautness and shine of the bodybuilder’s skin underscore bodily containment and impenetrability by drawing attention to the skin, and the body parts beneath, as a means to ‘“maintain body boundaries”’. [13] Connor notes that male bodybuilders rely on shine more than their female counterparts. He conjectures that this gender difference is the result of the fear of feminine disorder, so that the male bodybuilder can exaggerate the limit point of his bodily containment—the skin—while the woman must hold back her ripped muscles in case they should actually spill out and be rendered irrevocably abject. In Birrer’s photographs Linder’s body is not greased and glossed, but this is less from fear of bodily eruption than a challenge to this spectacle of containment. After all her photomontages rely on cuts into the surface of represented flesh. Her most famous work – featured on the cover of the Buzzcocks’ Orgasm Addict—shows an iron-headed, toned and greased female body, with a scar on the abdomen. The presence of this almost invisible imperfection announces both the break and repair of the skin, and the body. It is suggestive of a feminist politics of reparation, in which, as the rebuff of Freud in Linder’s lyrics dictate, ‘anatomy is not destiny, so why persist in training me.’ [14]

THE RED PERIOD

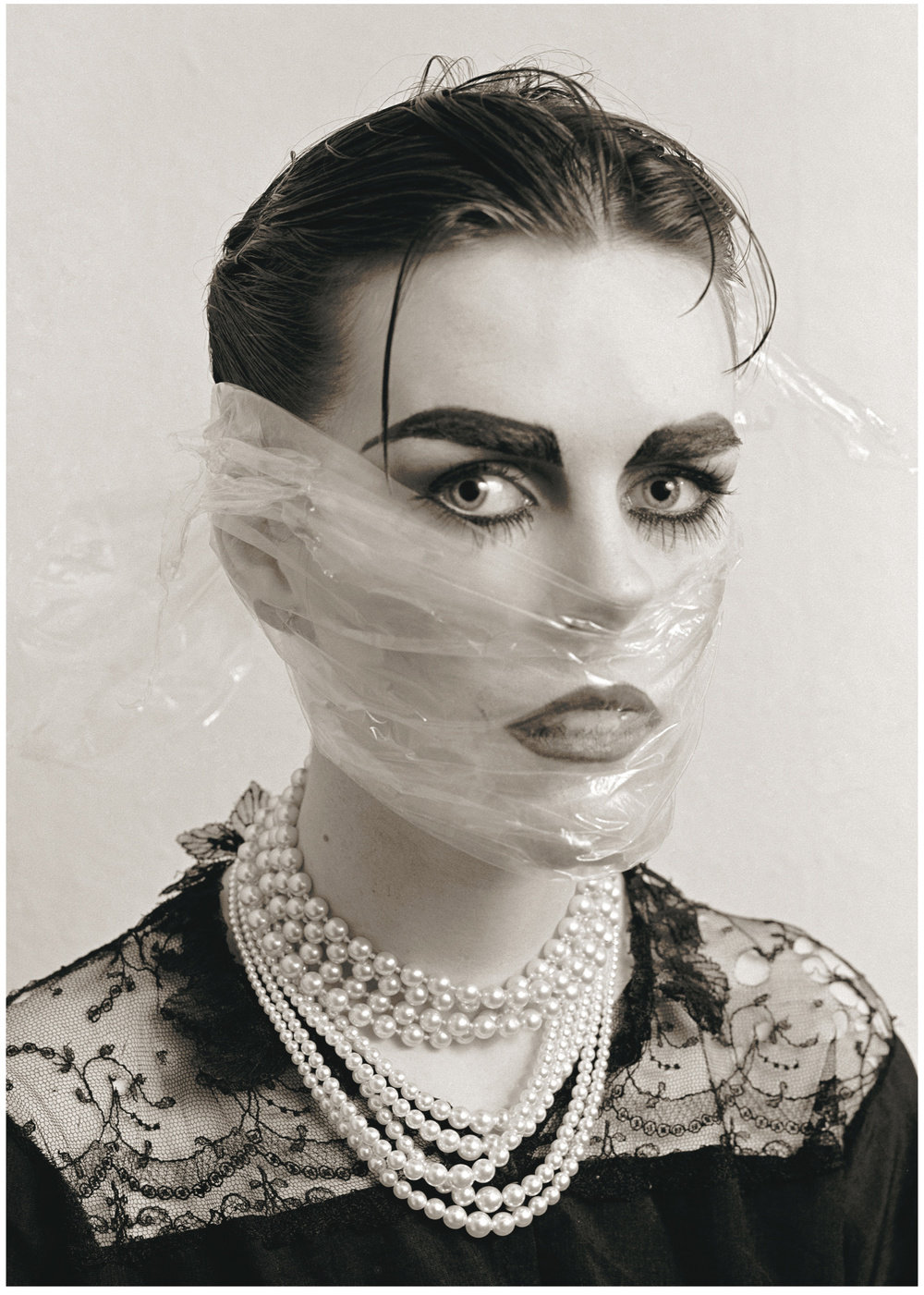

In 1977 Linder began to make music. She brought together a band called Bloodsports colliding the two meanings of the term: sex during menstruation and the upper-class pastime of foxhunting. Quickly the desire to de-anglicise took hold again and the band were renamed Ludus, the Latin word for play, game or sport. Her time as the lead singer of Ludus was an intensely creative period: she wrote, recorded and performed eight releases; designed the album artwork; and developed a new kind of self-portrait photomontage practice in which she entered the frame, often distributing these images with Ludus records. In works such as She-She (1981), Linder broke up her own image with heavy makeup, clingfilm and fragments of fashion editorial. She also per-formed a virginal stigmata for Mother’s Hour (1981) and what Buszek calls a ‘frumpy, DIY look’ of vintage clothes and wild ragged hair, the style adopted by other women musicians including Poly Sterene, for her Make-Up series (1982–3). In Ludus, Linder took centre stage, embodying a radical re-visioning of femininity after her photomontage interventions in visual culture.

Ludus gave Linder the opportunity to move beyond the image and to work with performance, language and voice, revivifying another aspect of dadaist and surrealist practice. The band’s sound had a typically post-punk style, with staccato beats and stark shifts between multiple rhythmic references. Critics compared Linder’s vocal performance to ‘machine gun’ fire, but just as often she croons in high frequency. In ‘Sightseeing’ from the EP The Visit (1980), both styles are combined and rotated against radically different rhythms, with lyrics that discuss the politics of representation:

When I can see through you

What can I see

Can I see me

Does my objectivity

Allow me access to your points of view Can you see what I see in you. [15]

Originally titled ‘Ways of Seeing’, the song invokes John Berger’s influential analysis of gendered representation in art and life. Other songs on the album invoke feminist politics like ‘Herstory’ and ‘Lullaby Cheat’, but the central theme Ludus revisited again and again was menstruation. In his NME interview ‘The Band That Gets Stranger and Stranger’, Paul Morley probes the band on their influence and reproduces the taboo. He asks: ‘Has she ever performed when she was menstruating?’ to which Linder replies ‘Yeah, right now.’ Morley’s reaction is: ‘That floored me,’ but Linder acknowledges that ‘it’s really simple. I just think it’s a resource that you can use.’ [16] Linder’s ‘use’ of menstruation as a ‘resource’ was a feminist transformation in which the taboo – note Morley’s embarrassment—was brought to the foreground. [17] Menstruation and its associations with hormonal mood swings appeared in the tense or angry effect of the songs, but Linder also redeployed synonyms for menstruation in their lyrics and titles. On album covers too, geometric women are trussed up in punkish bondage wearing menstrual pads, with line-drawn sneers and alluring smiles. A strict monochrome colour scheme, with bright blood-red accents, foregrounded what is usually, shamefully hidden.

Ludus performed a number of gigs including at the legendary, but macho, Manchester venue The Haçienda. Linder recalls that pornography used to loop ‘in a very casual and lazy way during the week when the club was empty.’ [18] She realised that this was the perfect place to perform with her band; she describes wanting to ‘strike… in the heart of it all.’ [19] The strike came with Ludus’ performance on 5 November, Bonfire Night, 1982. Infamously Linder roared through her set wearing rubber bondage gloves, a dress made of offcuts of meat and a net skirt, which was ripped off midway through the performance to reveal a dildo. Meanwhile Linder’s collaborators Cath Carroll and Liz Naylor spread blooded (red-painted) tampons on the floor and tables. Plans for a Bloody Linder cocktail to be served at The Haçienda’s bar, The Gay Traitor, were abandoned at the outrage of nightclub owner Tony Wilson. Her notebooks reveal more extensive, and tantalising, plans for a ‘menstruation mural’ comprising a corps of menstruating women and the orders of the moon, which would have transformed the space into a nouveau Cabaret Voltaire. Linder’s gender-de-fying performance of abject femininity was too much for The Factory, and her plans for a ‘Menstrual Egg Timer’ to come out as one of the series of Factory releases—‘Fac 8’—were also abandoned, with Wilson describing Linder as a ‘very weird lady.’ [20] To read Wilson’s epithet differently, swapping ‘weird lady’ with its Shakespearean synonym ‘witch’, Linder’s live and recorded Ludus performances were akin to rituals or spells of transformation.

Many of Linder’s lyrics for Ludus provide a language for her visual art. If ‘Sightseeing’ stages the politics of looking and being looked at, then ‘I Can’t Swim, I Have Nightmares’ describes something of the impossibility of just get-ting by when the sublimated drives de-sublimate. However, the Ludus songs don’t just describe the early work; they are also important for Linder’s late work, where they have been revisited and reused. This is most obvious in the reuse of ‘the bower of bliss’ from the song ‘Vagina Gratitude’ as a title for Linder’s most recent performances. ‘Bower of bliss’ is a synonym for vagina, one of many that make up the lyrics to ‘Vagina Gratitude’, which were appropriated by Linder from the Women’s Liberation issue of the countercultural magazine Oz. [21] The phrase comes from Edmund Spenser’s poem The Faerie Queen, where the ‘Bower of Bliss’ is a place ‘to abound with lavish affluence’. It is a place of seductive feminine abundance in an epic poem concerned with temperance; the bower stands in for women’s sexual autonomy, and perhaps also the unruliness of the menstruating body. In her performances Linder reclaims the phrase, creating a series of improper architectures in which bodies defy anatomical limits, and fragments of histories, sounds and ideas can be brought together in new, radical juxtapositions that characterise her more recent works in both expanded and two-dimensional forms.

I began this essay by emphasising the multiplicity and capaciousness of Linder’s practice. With this I suggested that her work is in excess to what is usually defined as visual art. And yet, her work does not just range around medium, genre or style but also moves through history—from art history to myth—and, crucially, her own autobiography. This is not linear or teleological but an accretion of references, an improper build-up that leaks and spills across her work, connecting parts like the glue in her photomontages. The other essays in this volume explore different aspects of her exploration and juxtaposition of fragments. While Alyce Mahon focuses on Linder’s use of flower motifs in her late photomontages, James Boaden examines the psychic entanglements of desire in Linder’s ballet photomontages and performances. Sarah Victoria Turner also explores Linder’s performance work, comparing her invocations of historic figures to a medium channelling spirits, and discusses Linder’s bringing forth of Helen Ede at Kettle’s Yard. Linder’s expansive collaging and her precise photomontages are not reducible to style; the multiple materials she transforms in her work—each with their own context and history—as well as the many people she collaborates with, trouble any singular identification. As such we must think of Linder’s work as more than a sum of its parts, an excess even. Linderism is Linder’s red period, impossible to date or contain in chronology, an improper feminine architecture, wary of taboo, and unruly.

[1] Dick Hebdige, Subculture: The Meaning of Style, London: Routledge, 1999 [1979]: p.17.

[2] See Maria Buszek, ‘Clothes Clothes Clothes Punk Punk Punk Women Women Women’, Design History: Beyond the Canon, edited by Jennifer Kaufmann-Buhler, Victoria Rose Pass and Christopher S. Wilson. London: Bloomsbury, 2019: pp. 87–110.

[3] Jon Savage, ‘The Secret Public’, in Linder: Works 1976–2006, Zurich: JRP Ringier, 2006, pp.8–15. See also Savage, England’s Dreaming: Sex Pistols and Punk Rock, London: Faber & Faber, 1991: p.298.

[4] Linder, ‘Northern Soul’, Linder: Works 1976–2006, Zurich: JRP Ringier, 2006, pp. 16–47: p.17.

[5] Simon Reynolds, Rip it Up and Start Again, London: Faber & Faber, 2005: p. xviii.

[6] Reynolds, Rip it Up, p.xxiii.

[7] Linder quoted in Savage, ‘The Secret Public’, p.14.

[8] See ‘Linder in conversation with Dawn Ades’, Linder, edited by Doro Globus, Manchester: Ridinghouse, 2014: pp.9–16 and 239–246, p.240–1.

[9] Buszek, ‘Clothes Clothes Clothes’, p. 97.

[10] Linder notes the influence of Mulvey and John Berger in ‘Linder in conversation with Dawn Ades’: p.48. Laura Mulvey, ‘Fears, Fantasies and the Male Unconscious or ‘You Don’t Know What is Happening, Do You, Mr Jones?’’, Spare Rib, no.8 (1973). Republished in Mulvey, Visual and Other Pleasures, Basingstoke: Palgrave, 1989: pp.6–13.

[11] Laura Mulvey, ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’, Screen, vol. 16, no. 3, Autumn 1975: pp. 6–18.

[12] Steven Connor, The Book of Skin, Cambridge: Reaktion Books, 2003: p. 57–8.

[13] Armando A. Favazza quoted in Connor, The Book of Skin: p. 57.

[14] Ludus, ‘Anatomy is not Destiny’ from ‘My Cherry Is In Sherry’/‘Anatomy Is Not Destiny’, Manchester, New Hormones, October 1980. Re-released on the double album The Visit + The Seduction by LTM in 2002.

[15] Ludus, ‘Sightseeing’, The Visit, Manchester: New Hormones, March 1980. Re-released as a double album The Visit + The Seduction by LTM in 2002.

[16] Paul Morley, ‘Ludus. Strange Band. Getting Stranger’, NME, 17 February 1979: p. 14.

[17] In this she was influenced by Penelope Shuttle’s and Peter Redgrove’s The Wise Wound: Menstruation and Everywoman, London: Victor Gallancz, 1978.

[18] Linder in Jess Scott, ‘An Interview with Linder’, Quinto Quarto Quarterly, no. 2 (August 2018), pp. 12–49: p. 35.

[19] Linder in Scott, ‘An Interview’: pp. 35–6.

[20] Wilson quoted on ‘Factory Records: FAC 8 LINDER STERLING Factory Egg Timer’, https://www.factoryrecords.org/factory-records/fac-8-linder-sterling-factory-egg-timer.php, last accessed 25 November 2019.

[21] ‘The Divine Monosyllable’, Oz Female Energy Issue, no. 29, July 1970.: np.