Blum & Poe Broadcasts presents free and public access to scholarship and writerly ponderings from our publications archives and network.

In focus this week—an excerpt from an interview with Masami Fujii conducted by Mika Yoshitake in the new publication Parergon: Japanese Art of the 1980s and 1990s (Los Angeles: Blum & Poe; Milan: Skira Editore, 2020).

"Much of the New Wave discourse, which in fact was in the process of relativizing and de-constructing the myth of modernism up until the 1970s, was bundled together within the framework of 1970s formalism and Mono-ha by the authoritative critic [Toshiaki Minemura]. Major media outlets almost grouped New Wave under the category of fashion based on consumer culture. However, the New Wave movement exceeded these frameworks. While engaging in pre-existing frameworks, the artists also pushed their outer limits, touching on the “outside,” and attempting to pry open a different world. This approach was distinct from formalism, conceptualism, and Mono-ha, which followed specific guiding principles; that was the New Wave as a postmodern development."

— Masami Fujii

Mika Yoshitake (MY): In your view, who were the key critical voices of the 1980s and 1990s?

Masami Fujii (MF): Artistic developments of the 1980s and 1990s are what I would call my specialty. Takashi Murakami has become the best-known practitioner from that time. It’s important to keep in mind the existing gap between our backgrounds, beginning with new art trends of the 1980s. Noi Sawaragi’s art criticism created the foundation of the canonical understanding of art in Japan from the 1980s through the 1990s and up to and including the present. He’s a strong critic and makes strong statements, but the complicated, intricate details of the 1980s were obscured by his fierce arguments. Murakami’s work has also been formative. I think it’s important to connect the two lineages. Sawaragi came along and created the basis for critique of the movement at large after the 1990s. Sawaragi moved to Tokyo and joined Bijutsu Techō as an editor in the late 1980s. But until then he lived in Kansai, and therefore he hadn’t followed Parergon or the artists who were part of the emerging movements in Tokyo surrounding Parergon. After Sawaragi relocated to Tokyo, he invited me to write for Bijutsu Techō. Sawaragi was great at what he did, and because his view was so convincing, there was never a counter-Sawaragi perspective. The gallerist Tomio Koyama was active then, and his gallery sprang up in the 1990s with roots in the 1980s.

MY: Can you tell me about your entry into contemporary art?

MF: Initially, my entry into the field dates to a time when I was involved in a Maurice Merleau-Ponty reading group. That was the first time I experienced reading a philosophical text, and it was a challenge. My friends who were art history majors were excited by Merleau-Ponty, as they thought philosophy could explain the importance of Cézanne better than art historical doctrine. I couldn’t get into it and blamed the difficulty partly on the translation. I came across the book Gendai Tetsugaku no Saizensen [The Front Line of Contemporary Philosophy] in a used bookshop in Kanda. I remember thinking, this must be more current than Merleau-Ponty, [and …] the book was literally enlightening. The increased clarity with which I saw the world was comparable to the effect of being struck by lightning. For three days I delved into the philosophy of Wataru Hiromatsu (1933–1994) and through that immersive experience I was able to comprehend Merleau-Ponty for the first time. Hiromatsu was a professor at Tokyo University in the 1920s, and the book was based on a roundtable discussion commemorating his Yamazaki Award for achievement in philosophy. That made it easy to follow, unlike a strictly academic work. That was my introduction to Hiromatsu’s philosophy and, in fact, also the starting point of my work as a critic and gallerist.

A teacher at my prep school once told me, “Your depiction of air and light is movingly beautiful. But your structure is weak.” I was unable to understand what he meant by “structure (kōzō),” and that bothered me. On my way home, I stopped at a bookshop in Ikebukuro, where I found the title Kōzōshugi [structuralism]. As I read that book I was shocked at how difficult it was—my reading up until that time had consisted of novels and textbooks. Naturally, theoretical texts by the likes of Claude Lévi-Strauss, Roland Barthes, Jacques Lacan, and Michel Foucault, explained in that book, were beyond my grasp.

MY: It’s impressive that you read these canonical texts independently.

MF: Because my curiosity was sparked, and I was determined to understand what these writers were explaining... When I opened Kōzōshugi, it was like being exposed to another language. So again, I turned to Hiromatsu whose writing was elucidating—crystal clear. I used it to understand Foucault and Lévi-Strauss. I was 19 or 20, and my friends were beginning to turn to contemporary art, which was conceptual art at the time. We would look at Bijutsu Techō, but I wasn’t completely sold on the types of critiques published in those days; to me they seemed too concerned with hierarchy. Art critics Shigeo Chiba and Arata Tani were just emerging. They were all serious, but I didn’t think the logic was flawless.

MY: How did you become a critic and what eventually led you to open Gallery Parergon?

MF: Artist Keiji Usami invited me to join his class at B-zemi [1] (“Basic Contemporary Art Seminar”) for free. My fellow colleagues and I created a contemporary art study group. Kōichiro Shiroda, the French literary critic, had an open seminar back then, and I joined that, too. Students from the master classes at Keio, Toritsudai, and Saitama University were in attendance and I created a semiotics study group with them. We studied Elements of Semiology (1964) by Barthes for about a month… You couldn’t learn these discourses at university; there were no specialized seminars yet. After studying Elements of Semiology, we felt prepared to tackle Jacques Derrida. In those days, his work was considered the most difficult to understand. So that became the next target for our reading group. Simultaneously I informally led the contemporary art study group. Eventually I felt comfortable in the world of criticism. At that time, it dawned on me that I could become a critic, though I was still aiming to be an artist myself. I read [art critic] Teruo Fujieda’s criticism of the art critic Marcelin Pleynet (b. 1933), and as a reader of Pleynet I strongly disagreed with Fujieda’s reading of the work. I submitted a “question sheet” to Fujieda-san, and to my surprise it got published in the pages of Bijutsu Techō. I was 24 and that was the first piece I ever published. Then everyone I knew suddenly began to urge me to become a critic; they said I was more talented as a critic than as an artist. A group of friends and I rented an inexpensive office and painted it to be a white cube. That became Gallery Parergon.

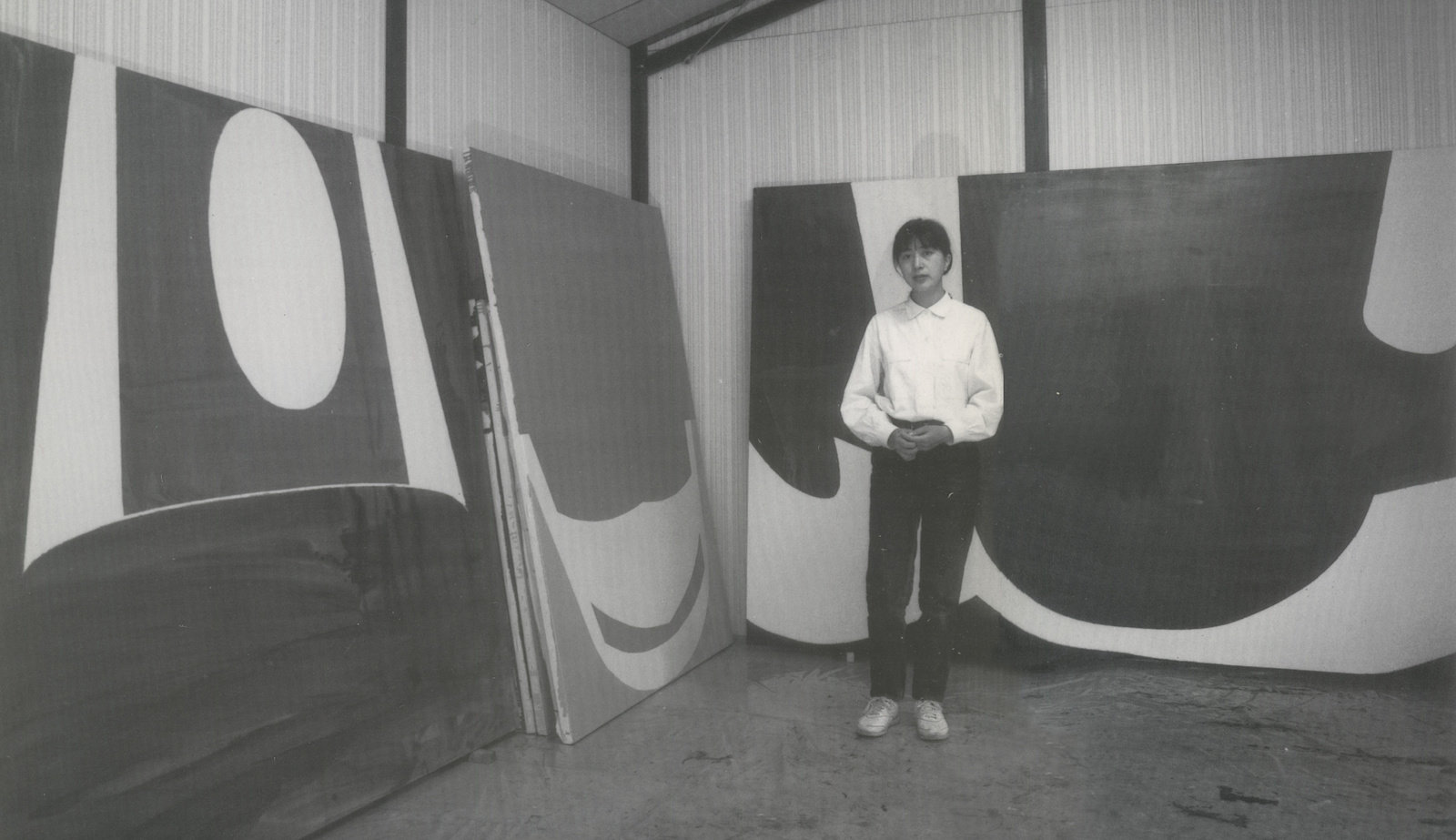

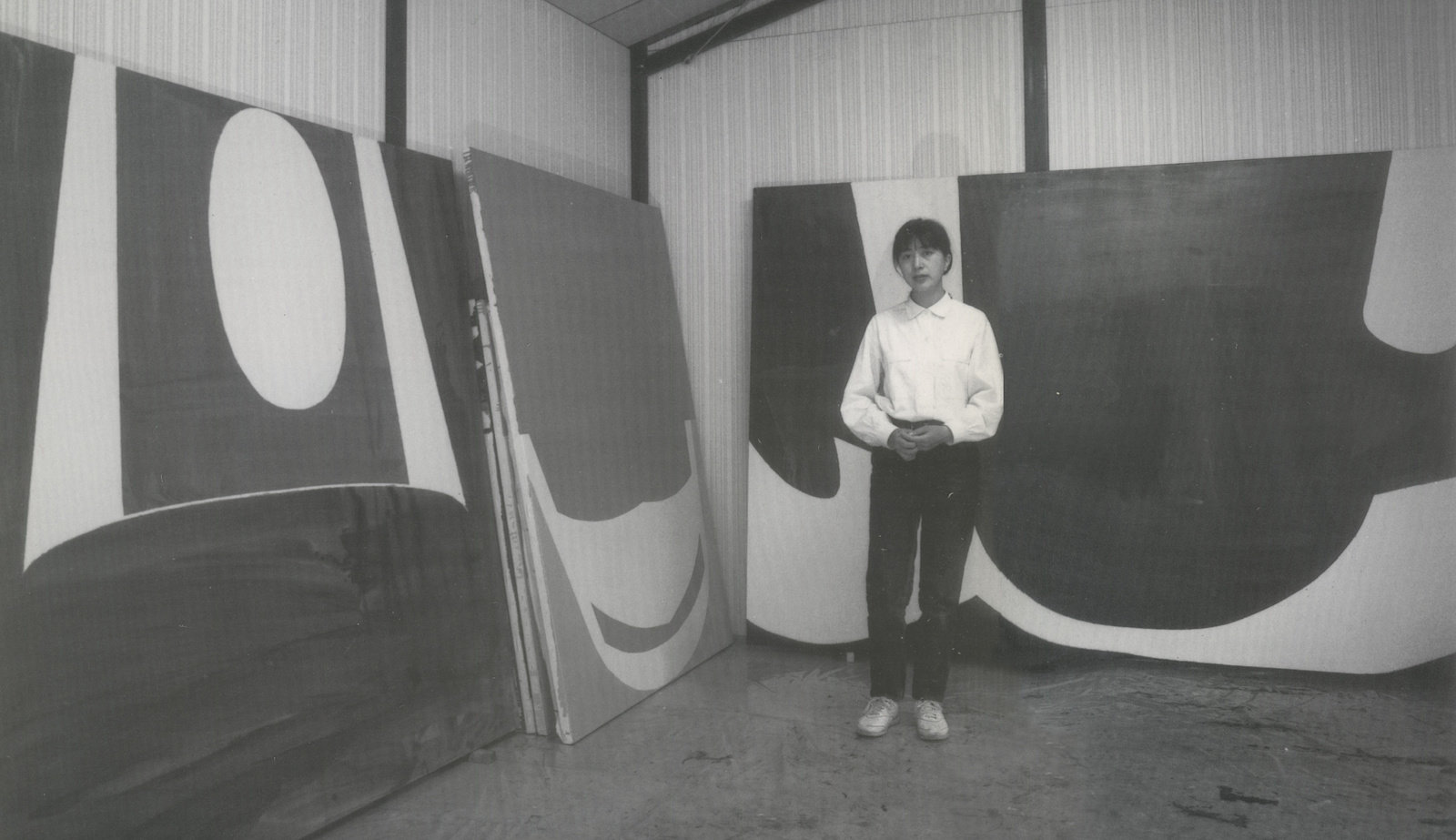

MY: Would were some of the first artists you showed at Gallery Parergon?

MF: Fellow artists in their twenties from the many study groups in which I was active and Kōji Enokura’s seminar students were the constituents of that group. For example, Kazumi Nakamura, who was an art theory major at Tokyo University of the Arts, came to Gallery Parergon on the recommendation of Enokura, who was his professor. Enokura wanted me to meet Nakamura, because, although as a painter he was still developing his technique, he had, as Enokura said, more passion and determination in him than any of the students who majored in oil painting. He was very hard working. He quickly became a fixture in the Parergon circle. He and Kenjirō Okazaki would often get into sparring arguments at the time. That was typical of what went on in the early days of Parergon. I think it was unanimously agreed upon that Okazaki was the undefeatable ideologue of the circle.

The first solo show I curated in 1981 featured the work of Mitsunori Kurashige (b. 1946, Fukuoka Prefecture). He was actually a generation older than all of us. But I started with him because his work fit the image of Parergon. I thought it embodied the definition of Parergon, because literally the framework of his works was made of fluorescent light. And that’s how Gallery Parergon started.

MY: After that you showed Keishō to Gengo [Form and Language] featuring Hisao Matsuura. There isn’t much out there in the way of photographic footage.

MF: In those times, my peers would gather at the gallery day in and day out. We lost a lot of sleep discussing everything.

MY: Was Parergon II run by students? Did it operate as a rental gallery?

MF: It was run exclusively by students. We were in our twenties so it was possible. The gallery functioned as a rental gallery. We made enough revenue that way to keep it running and to hire a small staff. We had some extra room for curated shows. We planned the curated shows with artists. Everyone would chip in to cover the cost, including the artists. Students would come by almost every night around the time the gallery closed, just to gather and talk among themselves. We ended up staying open until 10 p.m. or so. I managed for a while because I was young, but after two years I needed a break from that cycle. So Parergon II was managed entirely by students. Shin’ichi Sakai and Yasuo Miyake were both involved in Parergon II and they were a few years younger than Tadashi Kawamata at Tokyo University of the Arts.

Maki Gallery was located near Parergon. Actually it was Nobuo Yamagishi of Maki Gallery who said to me, “You should start a gallery.” Back then, all the galleries were in Ginza and Kanda. They were located so close together that if you were writing a series of reviews you could do the entire run in a single busy day. There were only about twenty. Now that’s unthinkable.

MY: Bijutsu Techō asked me to write about the new painting movement. Though key terms such as new painting and new wave were familiar, there were certain aspects that seemed strange to me. Chōshōjo [super girls] was one of the trends I didn’t fully understand.

MF: Shōko Maemoto did not appreciated being called chōshōjo. She was indignant when people started using that term. They thought it was trivializing and lacked style. I never heard the term used in artist circles, at least not favorably. It did prove a good source of jokes. People soon were telling each other whether or not Bijutsu Techō editors counted them among the chōshōjo. Mika Yoshizawa was thought of as central to the category. But again, I don’t think artists themselves ever voluntarily labeled themselves that way. Because of my looks [as a cross-dresser], those artists would tell me that I should be the leader of the chōshōnen [superboys] if chōshōjo were going to be a main feature of a magazine.

MY: I was introduced to chōshōjo through Sawaragi’s writing, and I understood that the concept had great impact on the scene.

MF: Yes. It was not proactively used by the artists; however, the category was not completely invalid. The previous generation that was deeply engaged in political activism of the 1960s and 1970s, including Lee Ufan and Toshikatsu Endō, who could be called the Mono-ha generation, became authorities and then lost momentum at the end. There was a rift between them and the next generation. Lifestyle itself had changed. Artistic objectives had changed. So, for instance, Tokiwa Gallery was a place where the previous generation, called the Dankai [group-minded] generation, and the young generation mingled. And artists of my age would debate with Endo and others his age. Endo-san would always say, “Your generation is much too lightweight.”

MY: That’s interesting and explains why Shinrō Ohtake used the term “too humid” when referring to the Dankai generation, including Mono-ha group members. So obviously the two generations had contrasting views of the art world.

MF: Exactly. That was the dominant opinion my generation had. In that sense, the category chōshōjo, which I believe originated with the Bijutsu Techō editors, makes sense. That was the way the older generation perceived our generation: as lightweight foreign beings, or a sort of extraneous matter. And that feeling was represented by the term chōshōjo. The person who first comes to mind when I hear that term is Maemoto. I saw her for the first time at the Kanagawa Prefectural Museum of Modern Art. I remember noticing this conspicuous looking young woman who had an entourage of seven or eight young male artists, and one of them was a fellow student I knew from B-semi, so we exchanged greetings. Maemoto-san, who was leading the pack, had long curly hair and in it had an ornament in the shape of a bird. I think it was some sort of toy that she used as a hair ornament. Her hair was curly and resembled a bird’s nest. Her work stood out just as much, especially in contrast to the standard in those days.

MY: Her work in Against Nature was very baroque.

MF: I think she was ahead of Murakami in bringing that particular influence, and also manga and anime references. It was slightly different from New Painting, and in a way she provided a precedent to what was later called super-flat and simulationism. She was the archetypical chōshōjo, it’s safe to say.

MY: What did you think of the so-called New Wave in general?

MF: Minemura and Fujieda were two formalist critics. Greenberg was adapted and Japanized, but it wasn’t properly rendered. I was more interested in Takashi Hayami’s writings. He was seen as being under the influence of Fujieda but was original. His Okazaki criticism was sharp, but I think Hayami was generally very encouraging to the artists involved in formalism. Fujieda was the authority, but Fujieda was self-righteously attuned to formalism.

Mono-ha was Toshiaki Minemura’s territory. He started using the term post-Mono-ha to categorize artists born in the 1950s. Except to his students, it wasn’t entirely clear what type of art that referenced, and he was generally resented. That, Fujieda’s minimalism, and postmodern art reacting to consumer society, including chōshōjo, were bundled together by the editors of Bijutsu Techō and used as a framework to contain the New Wave. Categories such as pop, postmodern, chōshōjo, and new painting already existed but were simplistically explained in that vein of New Wave. Artists felt it didn’t work. Essentially we, the makers of the movement, were inclined to push back and reject the label, although many of Minemura’s students may have endorsed it in one way or another. This isn’t a reflection on critics personally, but more on the framework. It was too broad, and the details got lost.

These were the problems that I encountered during my days at Parergon. That was I guess my reason to organize the exhibition Symbolic City, and I published my own theory in The Frontline of Contemporary Art. Broadly speaking I introduced three categories: neo-formalism, new image, and symbolic. In addition, the exhibition collaboratively organized with artists from Tokyo University of the Arts, Kyoto City University of Arts and Osaka University of Arts called Toshino nakano dōbutsu tachi [Animals in the City] was another effort we put together. We invited Akira Asada as a guest speaker during the exhibition. Atsuhito Sekiguchi who was a graduate of Tokyo University of the Arts was featured, and so was Kōdai Nakahara and Kenji Yanobe.

MY: Did you feature any artists from Kansai such as Nakahara and Yanobe at Parergon?

MF: I’m not sure if any Kansai artists were shown at Parergon. I believe not. We were small scale and financially were a shoestring operation.

MY: Nakahara mentioned collaborating through Gallery 16 in Kyoto. What about Ohtake?

MF: Ohtake was featured in a major gallery since he returned to Japan. Watari Gallery, the gallery later expanded into Watarium. Usually artists aren’t the best people to grasp the big picture of history, but I think artist Hideki Nakazawa’s book, ART HISTORY: JAPAN 1945-2014 is the most comprehensive in terms of capturing all the data from the footnotes of history. He featured Parergon in a major way in the second printing. He is an artist, so it’s his opinion, but I trust the data captured in that book.

MY: And was the selection of artists the most challenging aspect of running a gallery?

MF: I suspended my own personal interest for the time being and surveyed the artists I knew, […] and arrived at three main categories: image, symbol, and formal. I did not attempt to predict the direction in which each category would likely develop, nor did I explain my own critical position toward each category. I simply provided a map of what was going on in the contemporary field at that moment and suggested what those things potentially represented. That was my objective in publishing The Frontline. Of course, Kenjirō Okazaki criticized me for that.

MY: Could you explain further?

MF: He said to me, “Come on you need to show yourself more. Reflect your own taste.” In my view, he’s coming from the perspective of an artist, though he’s a theorist, too. Okazaki at that time had a bond with Hisao Matsuura, based on their theoretical ideologies. Meanwhile, I respected Okazaki and had a kinship with him as a friend, but I did not have an interest in sharing his ideologies. Personally, I felt that Okazaki was one of the most exciting artists I knew. I had other interests, too, personally. Tatsuo Miyajima was exciting, and so was Masumi Ōmura, who studied with Lee Ufan and was the type of artist who was making work that reflected an exemplary postmodern Japanese direction in art. Influential critic Yoshiaki Tōno championed Ōmura’s work and featured him in his exhibition series in the 1990s.

MY: I understand that there was no suitable forum for art criticism. Okazaki told me that was the reason he founded the magazine Frame.

MF: Even if there was, it always ended up being a competition between ideologies. Unfortunately, Minemura and Fujieda did not create an environment conducive to healthy argument for the sake of elucidating art criticism. I think [surrealist art critic] Shūzō Takiguchi’s generation saw the last of that type of environment for the arts. I wanted to take part in creating that kind of environment, but my efforts fell short, which is why I withdrew. No matter how hard I attempted to write serious criticism, no one was receptive, not even to the point of challenging what I wrote. I found the effort futile—the necessary climate just didn’t exist in Japan.

MY: But I believe there were some serious journals, architectural magazines, and theoretical journals like Episteme and Hihyō Kukan [Critical Space].

MF: Yes, Hihyō Kukan was the most advanced of the journals, but again, it was lacking a crucial element. I’m going to paraphrase Tatsuru Uchida, a well-known philosopher from the Kansai region who wrote a large number of philosophy and sociology books for general readers. Uchida wrote somewhere that despite the aptitude of the magazine, Hihyo Kukan was ill- fated. It was a doomed space, because it did not embrace diverse arguments. Whenever a new argument arose, the magazine would take it down, devouring it. It didn’t explore the interrelationships between the differences. It didn’t nourish healthy debate between alternative perspectives. So it consequently became a closed, introverted place. That was Uchida’s observation on Hihyō Kukan. Akira Asada and Kōjin Karatani may have been responsible for that. That situation may have reflected their particular qualities, seen through the lens of the larger set of traditions passed down in Japanese culture and philosophy since the Meiji era (1868-1912). I struggled with this culture every time I would invite someone to participate in a group… You would expect people to welcome new faces considering the topic. Instead, it would degenerate into whether you liked someone or not. The topic [criticism] was replaced with people bashing each other and saying things like "You criticize Fujieda, so you don't like formalism.” Of course, that doesn't make any sense. Yes, I am a harsh critic when it comes to Fujieda, and that is because I do not agree with the way he treated formalism ideologically. Treatment of formalism must be done through formal analysis, whether the subject is figurative painting, expressionism, or surrealism. Greenberg was often used as a reference.

MY: What about contemporary art historians in that lineage like Yve-Alain Bois…

MF: Well I think there’s some subtleties to consider with Greenberg and his successors. Greenberg is using Kant’s philosophy and aesthetics as a reference, and when you look at how Kant deals with aesthetics, it is not prescribing value to formalist methods as valid or invalid, but rather discussing how our experience with feelings, our emotional experiences, and the relationship between those experiences and our sensitivity relates to the forms of things. Kant’s terms are translated to “gou-mokuteki-sei” in Japanese which may sound a little arcane, but expresses the idea.

MY: In English that would be “purposiveness.”

MF: I guess you could say purposiveness is the sense of “fit.” The sense of fit supports the form in Kant’s theory. Therefore it is not about focusing on examining the form in a vacuum, removed from experience. As a model, decorative art may service as an example of that concept, because it demonstrates design made to affect the senses and bring out emotions. But that is nothing but an example. If we were to take a thoroughly formalist perspective and apply it to, say a Dali painting or an Arcimboldo painting, in other words, a work that is thought of as anti-formalist, we’re able to entirely understand the work with respect to its form. And we can use this lens to examine a wide variety of other issues. Formalist critique needs to be done in this way. This is why Fujieda-san’s style is often called a cut-and-dry form of criticism.

MY: In what way?

MF: He is just really just cutting through it all, separating the bad from the good.

MY: Judgement, in other words.

MF: Right. When you speak of “form” you are in theory just using the tools of formalism.

MY: It otherwise becomes a problem of taste.

MF: If we take that overly simplistic, cut-and-dry perspective on formalism, it’s a misunderstanding of it, and precisely because of that, I think that the form of Fujieda-san’s criticism, and the formal conditions of that criticism, are completely lacking when it comes to questions about the criticism itself. I thought that a lot of formalism, in terms of Greenberg or Michael Fried—whose criticism was directed at Greenberg—it shows that art criticism is difficult, and no matter how you go about it, your sense of taste comes into the picture sooner or later. Then the question becomes how far can you distance yourself from your own sense of taste? That’s what’s important. For instance with Rosalind Krauss from October, who distanced herself from Greenberg and Fried, developed a post-modernistic discourse eventually calling Greenberg and Fried’s work theology or metaphysics, if we want to put it in a modern way.

Krauss’s articles in October informed generations that came after her, but she was criticized in turn. Krauss’s argument was “specificity of media” but the term specificity is left ambiguous, along with the question of whether you are making a factual or value judgement when appealing to that idea. A lot of criticism was aimed towards Krauss and others in October because their methods failed to challenge political or social topics. Relational art with regards to the ideas illuminated by Nicolas Bourriaud was then criticized as a new tendency of speculative realism. Modern thought is nothing more than several phases of competitive selection surrounding a capitalist society. Blindly riding those tides can be dangerous.

As for me, I’ve been influenced from a very young age by postmodernism—Derrida and Hiromatsu who both demonstrated techniques used to distance themselves from the work they were critiquing, and those techniques were very clear and informative. At a young age, between Hiromatsu and Derrida, I got two completely contrasting, yet prime examples of these techniques. I had the good fortune to work with Hiromatsu for a number of years and I think I understood what his sense of taste was like. Hiromatsu was criticizedd by Asada Akira as being too simplistic. He liked to talk about Japanese folk music, and was old fashioned, with no awareness of cutting-edge culture, and perhaps that limited him ultimately. Nonetheless, Hiromatsu’s philosophy was clear, brilliantly rational.

Then I encountered, Jack Derrida’s text featured in the magazine Episteme mentioned earlier. It showed me something that Hiromatsu’s philosophy absolutely could not do, completely outside of the box. Hiromatsu attempts to reason with everything. Logical and clear. In that sense, you may call it structuralism, or formalism. Derrida said formalism would never be perfected. That there were some things absolutely beyond its capability. I was extremely lucky to have encountered Derrida and Hiromatsu at the same time. They both inspired me in different ways. I was given a philosophical foundation from Hiromatsu: When we perceive things, we can express the method so can empathize with the perceived meaning. And Derrida’s work, titled Parergon was enlightening. I remember one of my younger friends taking me to the bookstore. “I found a weird book. Come take a look at it” he said. It was the essay Parergon published in Episteme. The first sentence began with「 」. And that blank space at the end changed the course of my life.

MY: Yes, those blank frames. Around what year was that?

MF: That was ’76, ’75 or ’76. I was about twenty years old then. I found Hiromatsu when I was 19, and I encountered Derrida when I was about 20. I couldn't understand it rationally, but it was instinctively inspiring. I looked at this space framed by those two 「」marks. I had no idea what it was supposed to mean, but I knew it was something unusual, and it was a profoundly artistic experience. I had no idea what it was. More than words, blank spaces filled up the page. The margins.

MY: I believe the English version had been published in ’78, it might have been released earlier in Japan.

MF: It appeared in the first issue of Episteme.

MF: Osamu Takagi was close friends with Okazaki and was supported by the the critic Hayami. Takagi ran a magazine called Amplex. Critics like Hayami who wrote on formalism were primary contributors. Takagi held a unique position among Japanese artists. He was neither Mono-ha nor formalist. He was quite interesting as an artist, and a generation older than me or the Parergon artists. One day Takagi and I were in a conversation at Tokiwa Gallery and Takagi said to me, your gallery ought to be called Parergon. I remember feeling outdone by Takagi-san, though I’d had that idea already.

MY: How did Okazaki situate his theories and art practice at the time?

MF: Okazaki was a visionary and had the sense right away to carve out a place for his theoretical style to thrive. So he strategically developed a post-formalism rhetoric, a neo-formalism that developed into his famous work, Hardcore Modernism. It was a very carefully determined course of action and was successful. However, I couldn’t fully endorse that career choice. Or rather, I could accept it as his choice but couldn’t agree with him personally. I think we parted ways because of that. Once again, there were too many obstacles in Japan in the way of factions. I was uninterested in politics and was only interested in constructive criticism and positive arguments for the sake of empowering art. I love art, and that was why I started a gallery in the first place. And I loved coming up with ideas and debating theory. I couldn’t play a proactive role in the politics among artists and critics; it was too closed and inbred.

MY: What do you think makes it a challenge for Okazaki to be understood outside of Japan?

MF: It’s difficult because it’s highly contextual. Okazaki is seen as an opinion leader among a certain breed of intellectuals in Japan, and people follow him over long periods of time, so their understanding of his work is rooted in Japanese language and culture. Without that, his art is difficult to grasp. In fact, Okazaki’s aesthetic roots connect to Japanese traditions, such as an embrace of ephemerality. Artists who support Okazaki, I think, share that sentiment.

MY: He is anti-macho.

MF: Very anti-macho. Yes, exactly. So in a macho culture, Takashi Murakami is much more readily embraced than Okazaki. Okazaki’s aesthetics are about the virtues of in-betweenness. Neither here nor there. And it’s not very helpful that Okazaki’s cleverness has led him to fully understand Western art discourse. The general cleverness he possesses regarding this discourse may actually subtract from the inherent virtues of his own art.

MY: We are looking forward to presenting him in the United States. His work spans a long time period but manages to capture something very current and relevant in the globalized art world. We will show his relief work, paintings, and Zero Thumbnail series. As yet, I don’t know how comprehensive an understanding of the logic will come through in the States. That’s another separate issue. I find him interesting because of the depth of his logic and also the deeply interior sensitivity that so delicately counterbalances his logical side.

MF: I couldn’t agree more. Sensitivity sometimes gets in the way of his reception. Takashi Hayami was probably the only critic who got his work and fully supported it, while everyone agreed that he was a gifted theorist. I very much admire his painting of the contrasting gestural colors. My wife and I wrote the text for his earliest exhibition of that series in the 1980s. I am hoping that more people come to understand Okazaki’s art practice on a visceral level, not just its formal or strategic aesthetics.

MY: I know that Okazaki and Kazumi Nakamura come from quite different places, but both are already very popular with our audience. Both are logical painters, but they are in different conversations from one another.

MF: Nakamura had so much spunk and really took his early criticism and used it as best as possible. I admire him for that.

MY: Nakamura is a true purist.

MF: In that sense he is a very traditional thinker, but to his credit, because he used that to forge an indisputable position among his contemporaries. It didn’t stop him at all that others were more technically equipped when he first started. That’s an admirable quality. He had a persevering spirit. I meant “traditional” in that way.

MY: We are showing Yukie Ishikawa’s work, which you might call meta-photographic paintings. Photographs are enlarged and projected onto a canvas, then distorted. They are enormous. Contemporary painters have reacted very positively.

MF: In the United States?

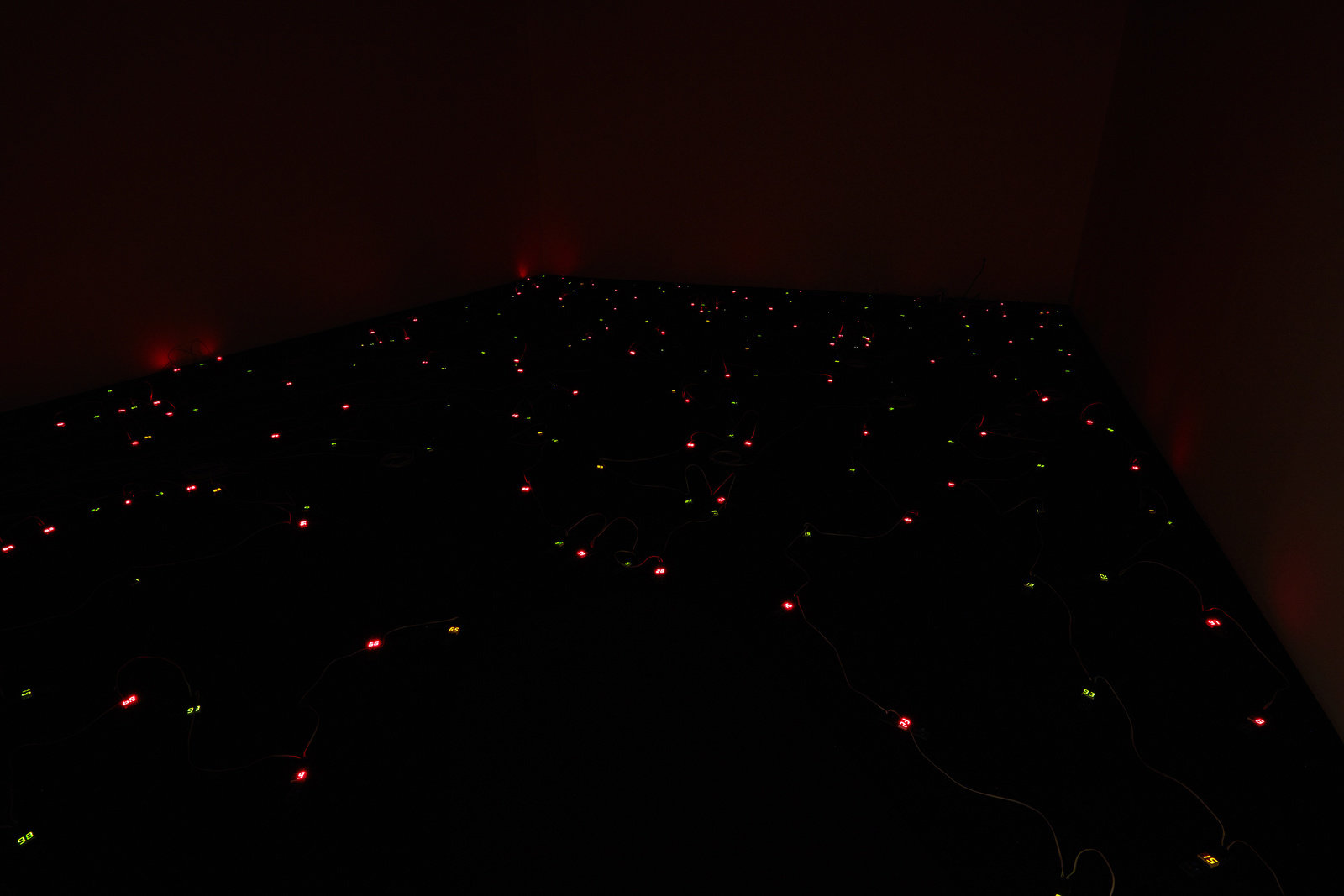

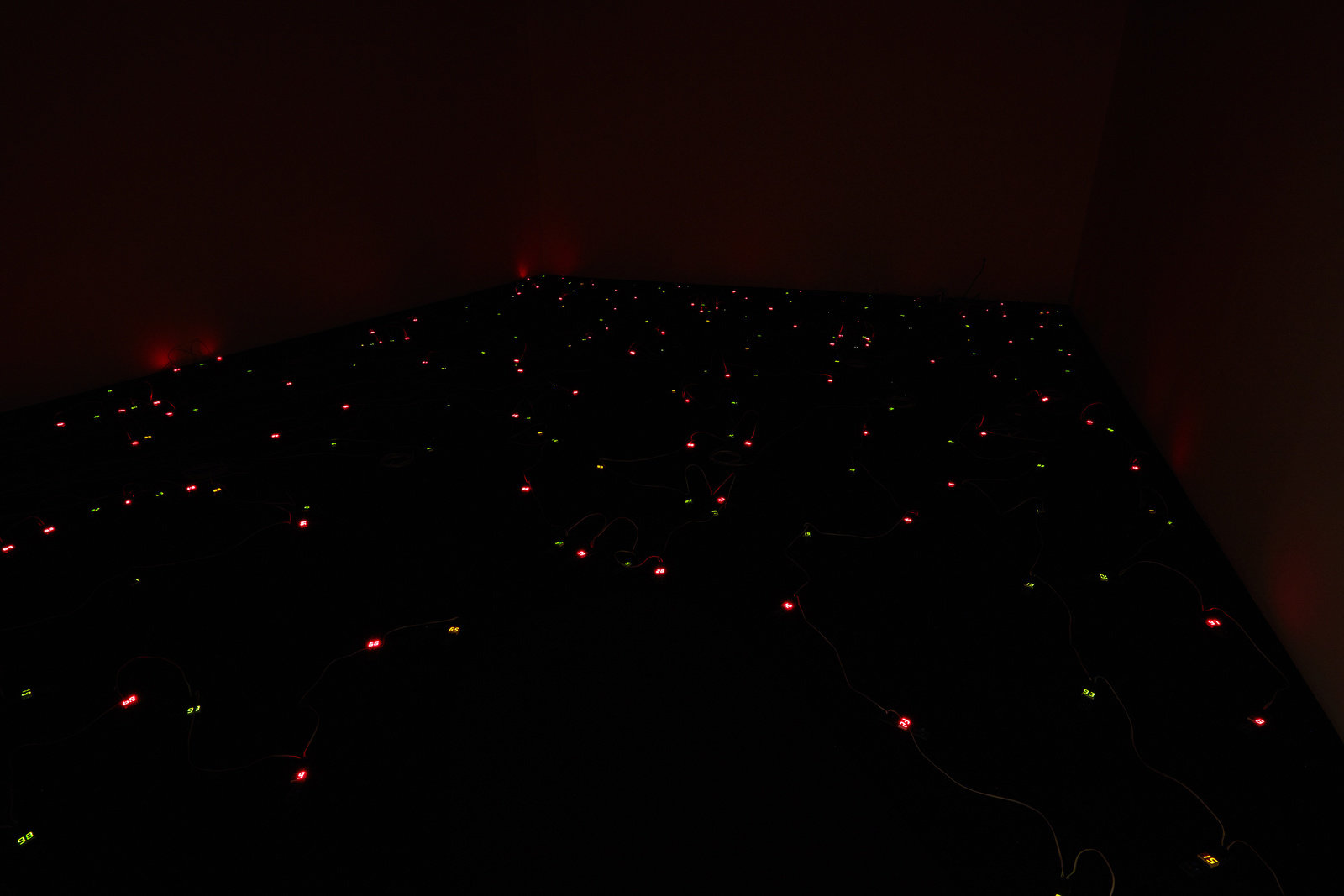

MY: Yes. We are also showing Sea of Time (1988) by Miyajima from the Venice Biennale.

MF: When I showed Miyajima at Parergon it was before he started making these works. He was collecting junk and connecting household electrics like toasters and radios. He would, for example, produce a chain reaction where the toaster’s switch would trigger the radio to start playing. So that would trigger another item and maybe then a cassette recorder would play a piece by Chopin. He would create new relationships, sort of like a postmodern [Jean] Tinguely. I liked his "junk relations." It was original.

MY: About creating a connection, relationships.

MF: That’s right.

MY: Well I think our time is up. Thank you so much for sharing your incredible knowledge and memories with us.

Translated by Miyuki Hinton.

[1] “B-Zemi” (Contemporary Art Basic Seminar) was an independent art school run by an abstract painter, Kobayashi Akio (1929–2000) located in Fujimichō, Yokohama. The curriculum was built around guest artists, who posed conceptual tasks for the students to discuss and experiment. See Kobayashi Haruo ed. B-Zemi ‘Atarashii hyōgen no gakushū’ no rekishi 1967–2004 (A history of B-semi “a study for new expression” 1967–2004) (Yokohama: BankART 1929, 2005).