© Sam Durant. With support from Blum & Poe and the Farrell Family Foundation.

Deep within the word “American” is its association with race.

—Toni Morrison

Nearly every civil rights leader has called for whites to be involved in ending racism—from Frederick Douglass, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, the Black Panther Party, to the artist Rick Lowe. Dr. King’s last book, Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community? could have been written yesterday. It is a call for collective, multi-racial action, for the joining together of Americans into a loving community against the death machine of racism, militarism, and greed. Sounds familiar.

Like life, racial understanding is not something that we find but something that we must create. What we find when we enter these mortal plains is existence; but existence is the raw material out of which all life must be created. A productive and happy life is not something that you find; it is something that you make. And so the ability of Negros and whites to work together, to understand each other, will not be found ready-made; it must be created by the fact of contact … The answer was only to be found in persistent trying, perpetual experimentation, persevering togetherness.

—Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

© Sam Durant. Collection of Hammer Museum, Los Angeles.

Suddenly it seems the discourse has shifted. Suddenly, it seems, we are not going to tolerate the police killing of African Americans any old time they feel like it and without so much as a slap on the wrist. Suddenly it seems a country that has always been upside down, appears as it truly is: a settler colonial nation founded on slavery and genocide with most of its institutions grown out of that originating violence. Suddenly it seems possible to change our budget priorities, to spend our tax money on more socially beneficial programs for instance, to even dissolve entire police departments. Suddenly it seems possible to treat drug use as a health issue rather than a criminal issue. Suddenly Black lives matter to whites in a way they didn’t before the murder of George Floyd.

But it’s not sudden. Our current moment of white awakening is a moment, just a moment, in a long, long continuum of the most profound courage, perseverance, brilliant intelligence, joy and love in the face of unimaginable suffering that is the civil rights movement. It is no understatement to say that the best of America are the people who have survived against all odds. Who, since the first slave ship reached American shores have resisted the country’s foundational violence and struggled for freedom. If America can be redeemed, it is through the white population following the example of the descendants of the Africans who arrived on the continent in chains. Along with the descendants of the real Americans, Native Americans. They have been leading us for generations and they will lead us still, if we can stop killing them, on the path to justice.

In the last few years groups such as Black Lives Matter, Critical Resistance, Equal Justice Initiative, The Southern Poverty Law Center, and activists like Angela Davis, Ruth Wilson Gilmore and Reverend Dr. William J. Barber, II (to mention just a few out of the thousands), have invested hard work and sacrifice and created the possibility for what appears as a sudden awakening in mainstream society. Because of this work, research, and organizing, it is possible for the brutal murder of George Floyd (and the many, many other victims) to catalyze this potential turning point, this transformational moment. One that needs to be nurtured, supported and grown. Whites need to be reminded, work needs to be constant against forgetting, against backsliding and toward the more just and loving society we strive for.

The past is never dead. It’s not even past.

—William Faulkner

I live in Germany and I have learned how a country can make confronting its history part of everyday life, part of one’s identity. I came here in no small part for this reason, to see how they have dealt with their monstrous past and how I can learn from their efforts. It’s not perfect by any stretch, but the way German society takes responsibility for what it did—for the Shoah, the Nazi crimes—and makes sure every day that it is not forgotten, holds much for Americans to learn from. The Germans have also set up institutions and processes for reparations to the people (and their descendants) who they looted, displaced and murdered.

Bryan Stevenson of the Equal Justice Institute cites Germany when he talks about his remarkable National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama which remembers the victims of lynching in America. In Germany it was understood that the burden for remembering must be taken up by all Germans and especially those from the majority white population who are not Jewish. While many of the memorials to the victims of German crimes and the monuments to those that resisted were realized by Jewish artists, perhaps the majority have been done by non-Jewish artists. There are many reasons for this, among them the idea that non-Jews must always be forced to remember and must participate directly in the many forms of remembering. Another reason is the unfairness of asking the victims of the crimes and their descendants to shoulder the burden of remembering for the society that is mostly non-Jewish. Of course, the door must always be open to Jewish artists first, their expression must always have equitable space. If one draws the analogy across the Atlantic to the racial dynamic in the United States, it points to the necessity of the white population taking on the lion’s share of the work of ending white supremacy, recognizing and remembering our ancestor’s crimes, and then beginning the process of real, meaningful reparations on a structural and institutional basis. I have always maintained that white supremacy and racism must be actively resisted and ultimately dismantled by whites. The fight should certainly be led by African Americans, Native Americans and other minorities, we must be guided by those who have suffered, but it is whites as the creators, enforcers and current benefactors of a corrupt and violent system who need to do the work and do the work continuously so that we never forget. And like in Germany, equitable space must always be there for minority artists’ expression. As James Baldwin reminds us, white supremacy distorts and destroys everyone’s humanity.

It is so simple a fact and one that is so hard, apparently, to grasp: Whoever debases others is debasing himself.

—James Baldwin

© Sam Durant. Collection of Hammer Museum, Los Angeles.

I have participated in many discussions about these issues in the past twenty years and have heard repeatedly from non-white and minority voices that they are sick and tired of having to teach the white folks about racism, to always carry the burden of both the suffering and the duty to represent it for those who are either unconsciously or actively performing the oppression. In our current moment of sudden awakening many galleries and museums find themselves in a bind. Shouldn’t the galleries put the African American artists they work with (if they represent any) out in front? Shouldn’t museums ask their non-white and minority staff (if they have any, many do not) to make statements in support of Black lives and against white supremacy? But doesn’t this both burden those African American artists and cultural workers with doing the work of representing the problem while also running the risk of seeming to absolve the institutions of their own complicity in institutional racism? Some will say that it is still important that African American artists must be given visibility and opportunity even so and especially now. This dilemma reveals another aspect of how white supremacy corrupts our institutions. They are damned if they do and damned if they don’t. This is the art world that all artists work within, and as such we are also damned if we do and damned if we don’t.

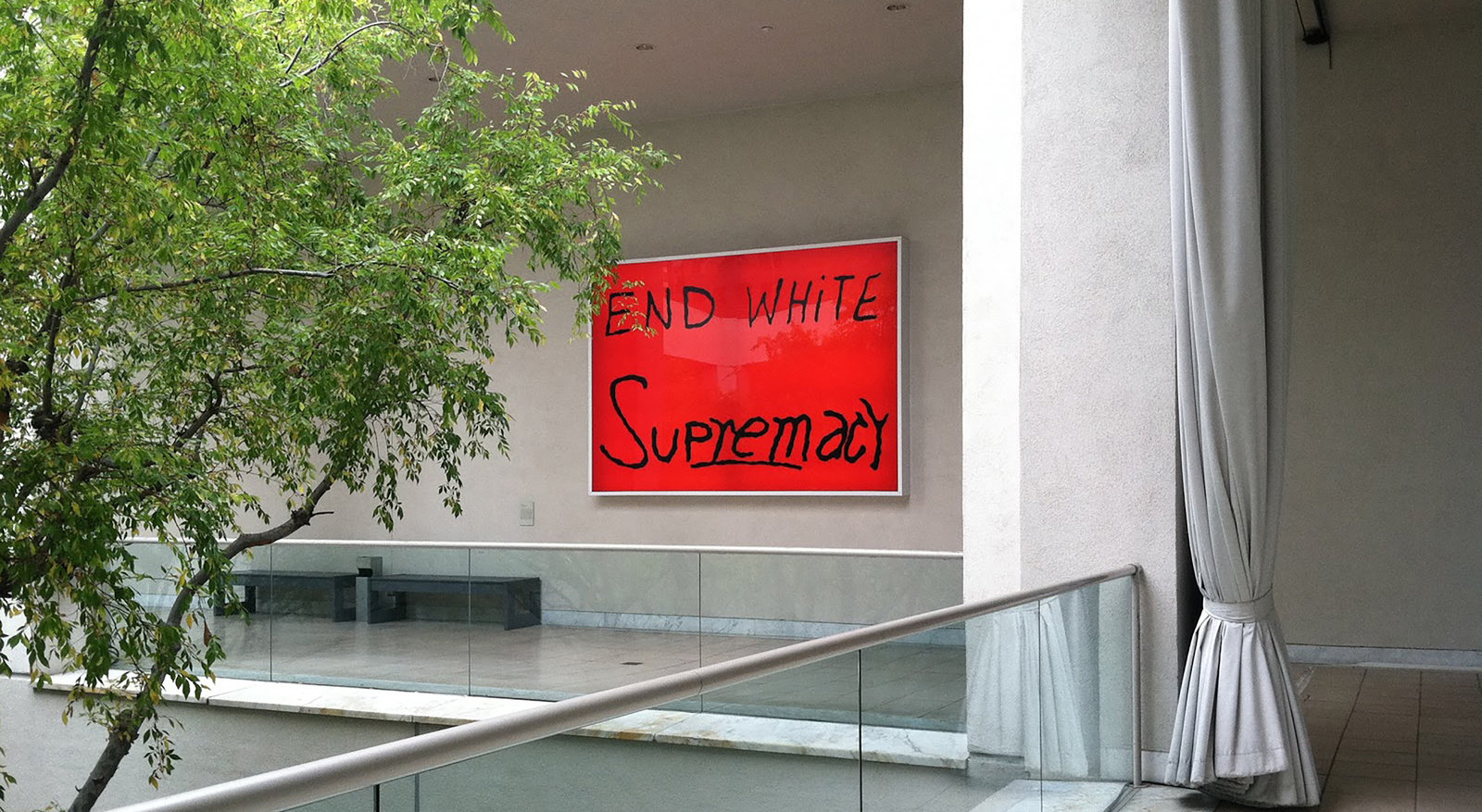

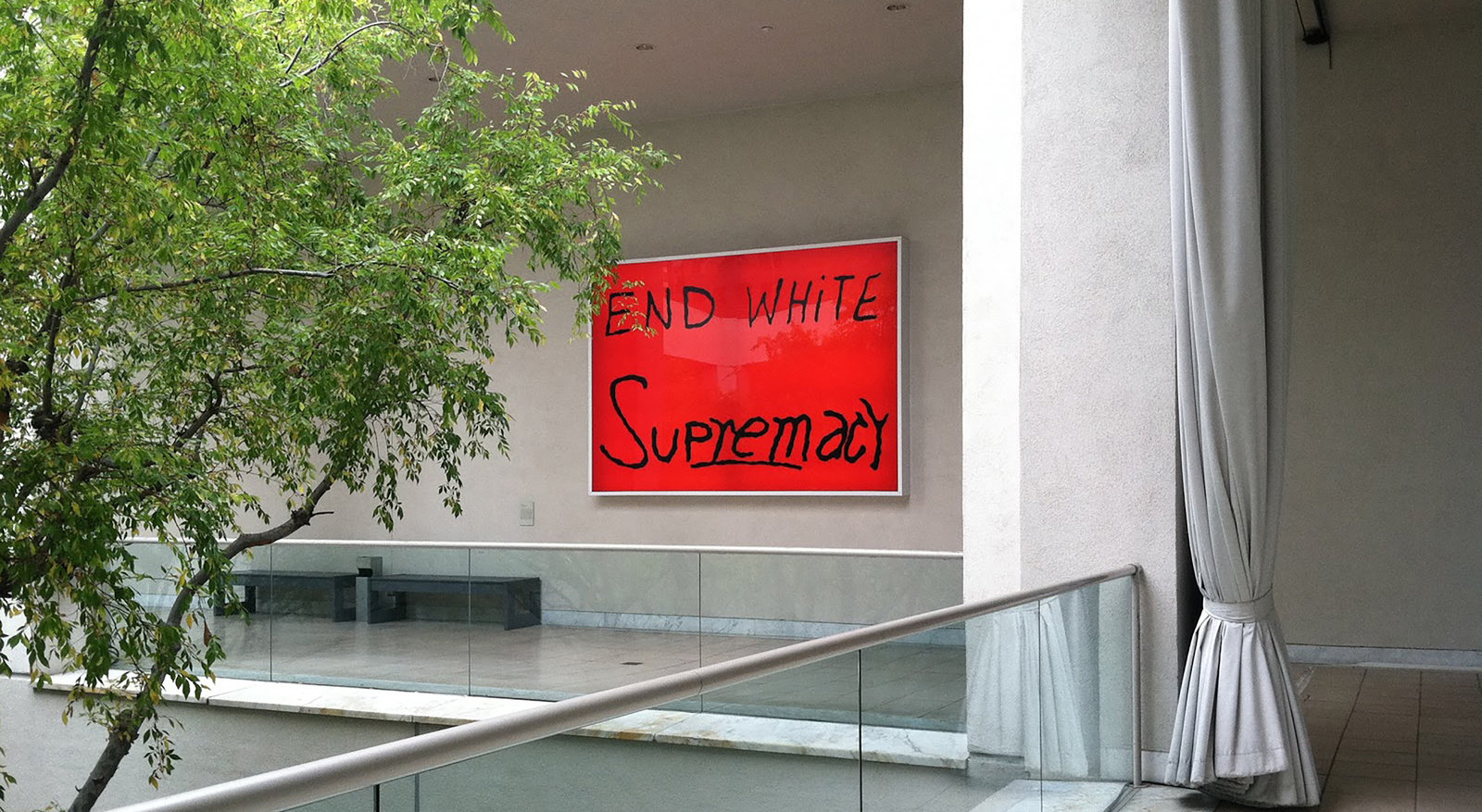

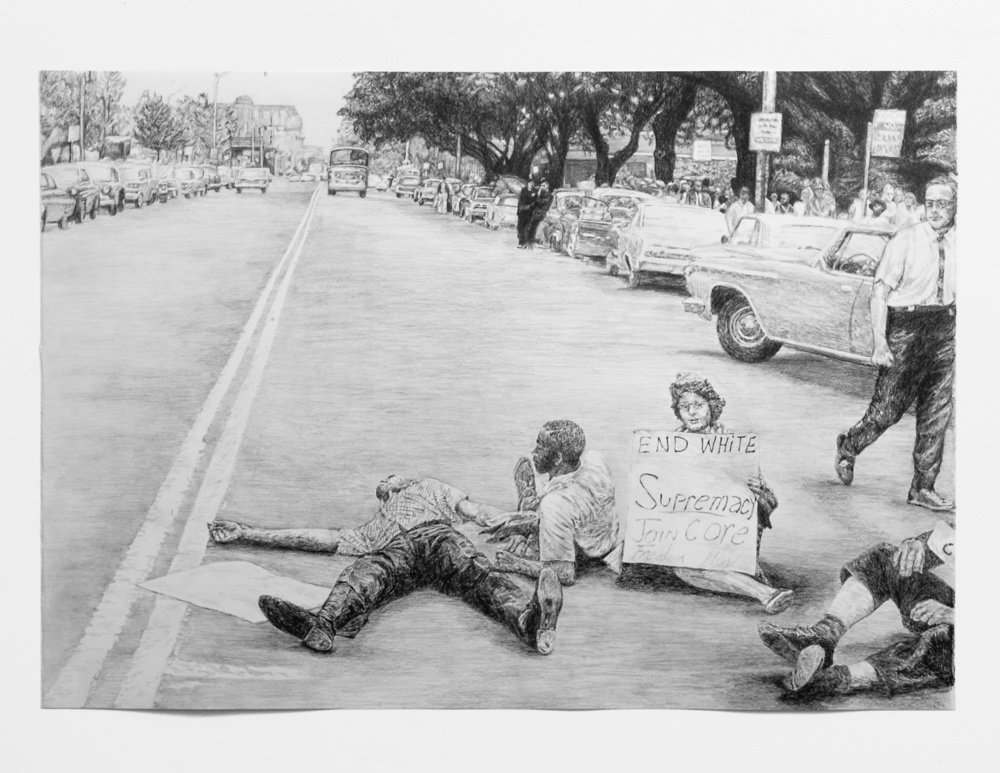

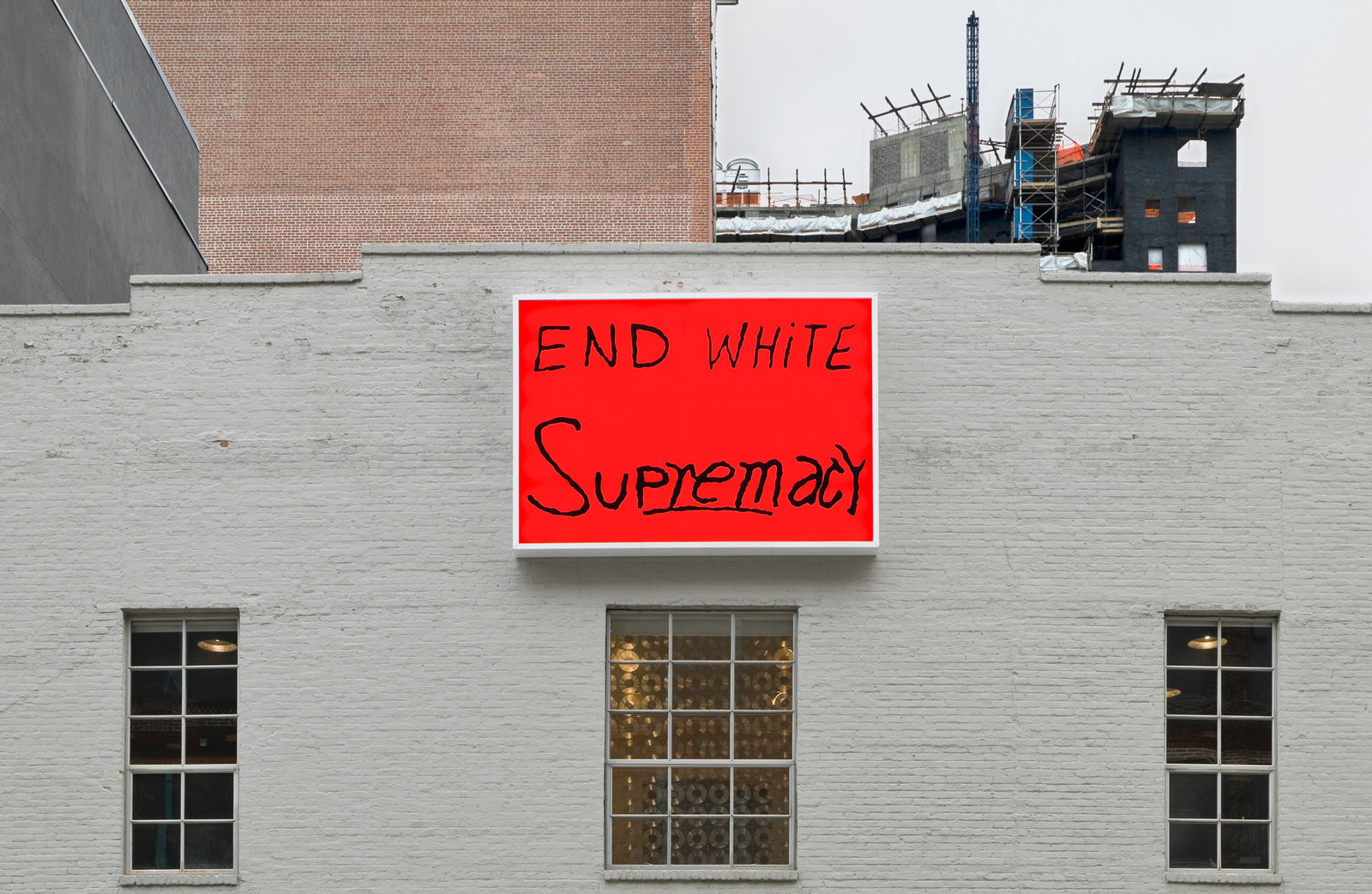

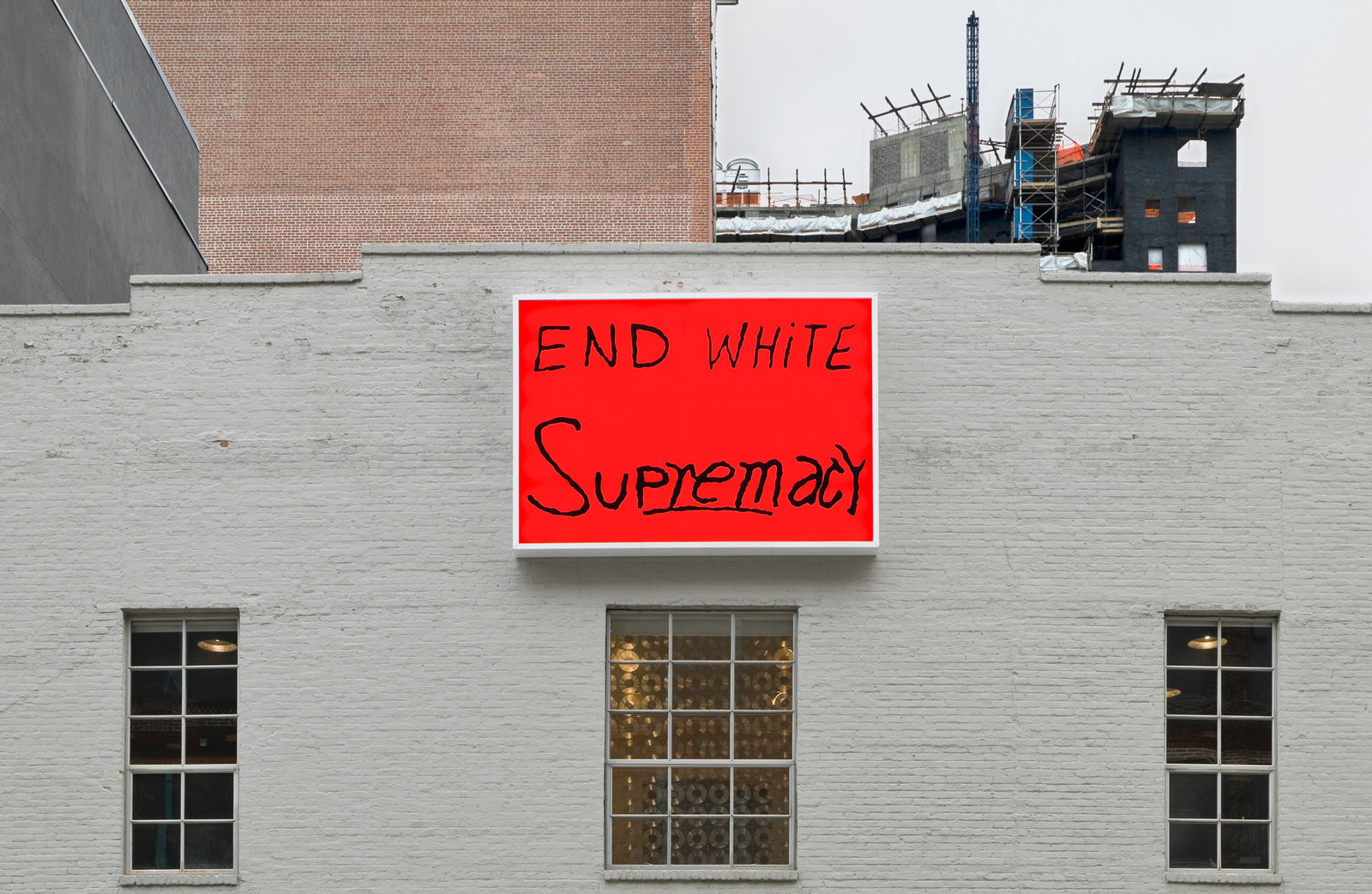

This impassioned plea to “end white supremacy” was originally handwritten on a sign and carried during a civil rights protest in New York in 1963. For several years Sam Durant has used archival photographs of protests around the world as source material for both drawings and text-based pieces rendered as large-scale light boxes. Recreating these found photographs in carefully detailed graphite drawings that record social and political unrest, the artist then often isolates the messages articulated by the protesters and puts them into formats typically used for commercial signage to pose questions about the role of language and how meaning is constructed. Keeping the handwritten quality of the message intact, Durant’s sign stays faithful to the personal expression of the statement while also underscoring the urgency of the sentiment within the public sphere.

—Hammer Museum didactic, 2017

As a white American man, I have a responsibility to participate in this moment of uprising against state-sanctioned violence and anti-Black racism; as an artist who has researched and cared deeply about social and racial justice and American history for more than two decades, I feel even more compelled to participate. I have been accused of many sins: cultural appropriation, profiting from others' pain, telling a story that is not mine, mansplaining, whitesplaining (is that a real term yet?), among other unsavory labels. But I hope my words here argue against such epithets, those who know me certainly know how deep my commitment to justice is and how hard I fight not just with my artwork but within all the institutions I participate in for racial equality. I have always stated that my work is directed primarily at white audiences who may be unaware of the uncomfortable truths of the race’s often buried history of administering systems of oppression, hegemony, and public violence. This work is of course intended to also be open to all viewers, not just whites. This work is produced with the idea that through an aesthetic experience the world can be revealed as it really is. Through representation, the status quo (of white supremacy, for instance) can be glimpsed by those who have never been aware that what we call “reality” is in fact a construction. A construction that can be changed. In that revelatory moment transformation is possible. As Herbert Marcuse proposed, in order for the world to change, those who would change it must themselves be transformed. And the aesthetic realm is one of the few places left for that possibility to arise.

End White Supremacy

Sam Durant, 2020

Photo: EPW Studio. © Sam Durant. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York.

Sam Durant is an interdisciplinary artist whose works engage a variety of social, political, and cultural issues. His methodology is research based but with an emphasis on social engagement, often working with communities and groups in collaborative and performative formations. Growing up in Massachusetts in the 1970’s he experienced the radical pedagogy of A.S. Neill, Maria Montessori, John Holt, along with anti-war demonstrations and the desegregation of the public-school system. Exposure to an educational culture emphasizing democratic ideals, racial equality and social justice created the framework for Durant’s artistic perspective. Often taking up forgotten events from the past, his work makes connections with ongoing social and cultural issues.

Durant’s interest in monuments and memorials began with Proposal for Monument at Altamont Raceway, Tracy, CA (1999), referencing the violent end to the infamous free concert and arguably to an era; and continued notably with Proposal for White and Indian Dead Monument Transpositions (2005), re-contextualizing memorials to victims of the conquest of North America; and more recently with Proposal for Public Fountain (2015), a marble work depicting an anarchist statue being blasted by a police water canon. Earlier works excavated subjects as diverse as the repressive practices of Modernism, the death drive of ’60s and ’70s pop music, and artist Robert Smithson’s theories of entropy. Contemporary examples of his oeuvre encompass subjects such as Italian anarchism, cartographic histories of capitalism, gestures of everyday refusal, and the meaning of museums for their visitors. Recent major public art projects include Labyrinth (2015) in Philadelphia, addressing mass incarceration; and The Meeting House (2016) in Concord, MA, focusing on the subject of race in colonial and contemporary New England.

In 2007 Durant compiled and edited the monograph, Black Panther: The Revolutionary Art of Emory Douglas (New York: Rizzoli International) and curated the exhibition of the same name at MOCA, Los Angeles and the New Museum, New York. He has contributed catalog essays to Marcos Ramirez ERRE (Mexico City: Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes, 2011), Siah Armajani: Follow the Line (Minneapolis: Walker Art Center, 2018) and Hans Haacke: All Connected (New York: New Museum, 2019). From 2005 to 2010 he was a member of the collective Transforma Projects, a grassroots cultural re-building initiative in New Orleans. In 2012-13 Durant was an artist in residence at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles where he collaborated with the education department to produce a discursive social media project called What #is a museum?. This became a solo exhibition in 2016 at UC Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, Berkeley, CA.

Durant’s work has been included in numerous international exhibitions including Documenta 13, the Yokohama Triennale, the Venice, Sydney, Busan, Liverpool, Panama, and Whitney Biennials. His work can be found in public collections including Fonds National d’Art Contemporain, Paris; Hammer Museum, Los Angeles; Museum of Modern Art, New York; Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; Project Row Houses, Houston; Stedelijk Museum voor Actuele Kunst, Ghent; Tate Modern, London; among many more. Durant is based in Berlin and Los Angeles and teaches art at Hochschule für bildende Künste in Hamburg and California Institute of the Arts in Valencia, CA.